A small red flower bloomed by the side of the road. The Stranger paused, following the trail of red drops down the slope. Pine needles crunched underfoot. The broken moon hung in the sky, as deformed and grotesque as a clown mask. The Stranger had been travelling for a long time, and was to travel for a long time more. He shifted the long rifle on his back and then drew it, cautiously. He proceeded down the slope.

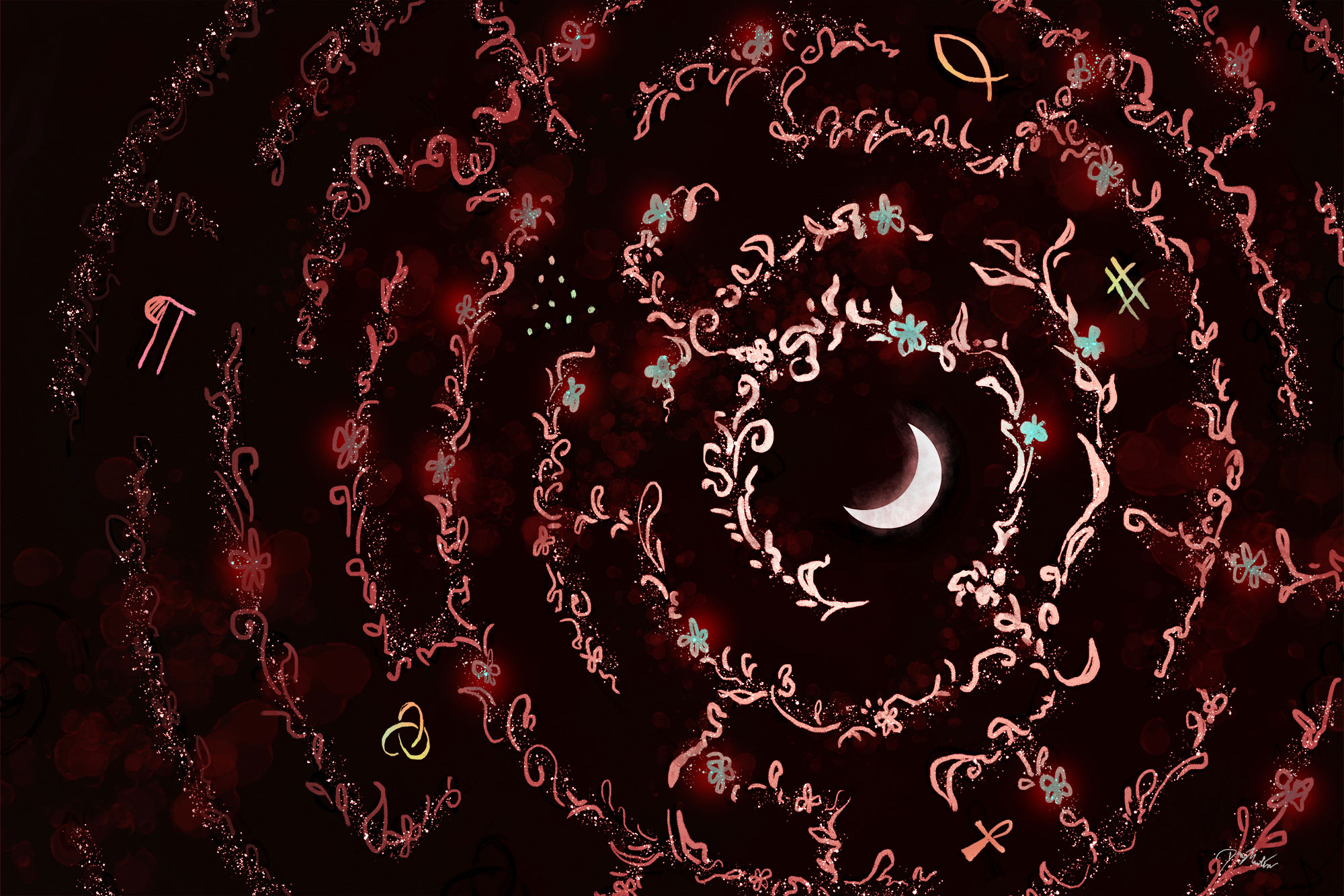

The night sky was clear and in the distance he could see the first signs of a coming storm. Loose ankhs flashed on the horizon, and glowing ichthys fish burst briefly in vibrant blues and reds. The storm was coming, but it was still a long way off. The air smelled fresh and sharp. The Stranger discerned pine resin, gunpowder, blood. The pine trees were not tall and the needles brushed against his face as he passed through the trees.

When he reached the clearing he stopped, and then he put the rifle back over his shoulder. He stood stock still, looking at the bodies.

The massacre must have taken place only recently. There were eleven bodies, and some had been shot in the back and some from the front but either way they were all dead. Some had tried to flee their attackers and were gunned down, and some stood stoically and awaited their death. The Stranger smelled greasepaint, candyfloss, gunmetal oil. The tattered remains of a yellow balloon lay on the ground.

The Stranger examined the scene of the massacre. He had been witness to such scenes before, in other places, far away from there, but he never grew indifferent to such a sight.

Eleven clowns lay on the ground. Unusually, while five were Augustes, four were Whitefaces, and two were Hobos. The two Hobos had stood up to their attackers, and the Stranger noted the remnants of custard pies thrown at the attackers.

He took everything in methodically. Each of the clowns had been scalped, and the Whitefaces’ red ears had been sliced off, as were some of the Augustes’ red noses. The Stranger knew it was the habit of bounty hunters to do this, to create a brace of the ears and noses for easy transport and to display; and that they would be aiming to collect a bounty for this, the assassination.

He also noted that not all had been taken. Perhaps they had been interrupted, or were spooked, as they were collecting their trophies. He glanced around him a little more uneasily. The symbol storm was still distant but it could herald the coming of other forces, though sometimes it did and sometimes it didn’t.

None of this was, strictly speaking, his business, but he determined nevertheless to make it his.

The Stranger went back up the slope and retrieved his horse. He spurred it down, but around the copse of trees, and he noted the hoof prints of the horses and the direction they went.

The riders went in a hurry. Something had spooked them, he decided. The hooves had scattered pebbles and dust as they ran at full gallop from the scene of the massacre. The Stranger noted five sets of hoof prints on the ground. He spurred his own horse to a light trot. He did not bury the clowns. Golden spirals and tetractys flashed briefly overheard on the horizon. The Stranger rode away into the distance, following the scalp hunters.

•

The storm passed harmlessly to the west during the night. The Stranger rolled his bedding in a sheltered spot under an outcropping of rocks which resembled a grasping, if somewhat deformed, six-fingered hand. A ring of dark moss around the third finger resembled a wedding ring. The Stranger did not light a fire. The wind howled through the rocky fingers, but the Stranger had long grown used to the sounds of this world, and he slept soundly enough. When he woke, a yolk-yellow sun had risen in the sky, and in its light he could look all across the Escapement.

At his back, the small pine forest that was nestled under the low-lying hills remained as it were, hiding within it the horrors of the massacre. White tendrils of clouds stretched across the sky. To the east, the Stranger could see a vast edifice, a gigantic, half-buried machine-like structure jutting out of the ground. The edifice resembled a sort of conical device or passenger ship, made of some dark metal in which glittering gems could have been windows or other, less explicable features. The ground around the edifice was bare.

To the south, the Escapement spread empty until it reached the distant horizon. A flock of dark birds flew into the sky, tiny black dots moving with an unknown purpose of their own, heading farther south. The remnants of a road snaked north-east across the land. The Stranger ate a frugal breakfast of dry hard cheese and stale bread, and then he remounted his horse and continued to follow the scalp hunters’ trail.

They had ridden hard through the night, he surmised, and had built up a considerable lead. But he wasn’t in a hurry. The Stranger had travelled for a long time and was destined to travel for a considerable time more, and if he had learned nothing else he had learned patience. He fed and watered his horse and then remounted. They rode slowly, over rocks and brambles, following the contour of the low hills, following the path of the scalp hunters. As the sun rose higher, yellow and eggshell white paint smeared across the sky, and the Stranger pulled his hat low over his face. When he found the murderers’ campsite, the dead fire they had left behind felt still warm, and he saw the grooves in the earth where each of the men had slept. He continued on his way, scanning the desolate landscape for possible sites of materiel, but he did not see any.

He rode from sunrise to sundown without encountering a living soul. Only once was he startled, when the sun began to dip in the sky and the air grew cooler. He had looked west, where the storm had passed, and for just a moment, it seemed to him that a shape appeared there, immense against the sky: an immovable stone statue, as tall as a mountain, sat in a carved throne; and the sun shone over its head like a crown.

At the sight of this apparition the Strange spurred his horse into a canter, and when he next looked the giant figure had disappeared as though it was never there. That night, when he camped in a dry river bed, the Stranger heard the distant sound of fighting: booming, maniacal laughter that echoed magnified across the Escapement, part-sob and part-screech, and the thump thump thump of giant feet, trodding on the ground, and the terrible ticking of clocks, and this was accompanied, or perhaps accentuated by, irregular bubbles of sudden, and somehow awful, silence, a sort of negative sound which had the horse whinnying, but in a kind of quiet desperation. The Stranger listened to the sound and unsound of battle as it raged on for hours, until at last it grew faint and passed on, the two unseen armies skirmishing to the west. In the morning a blood red sun rose and under its light the Escapement appeared smeared with a coating of red mud, and the Stranger knew that the ground farther to the west would be littered with materiel, but still he kept to his course.

By around noon he came to a small crystalline brook flowing in between two green hills. The horse drank greedily and the Stranger drank sparingly and filled up his skins. The land changed over the past few miles and in the air he could smell distant smoke, hints of custard, and fresh horse shit. By the side of the brook he found a circle of stones engulfing another recent fire, and in this one the coals felt warm. The Stranger, thoughtfully, checked his rifle and his revolvers. He turned to check on the horse next, who was feeding on the grass by the bank, when he saw the child.

The face that stared at the Stranger from the bushes on the other side of the brook was pale white and startled. The child’s eyes were large and solemn, the mouth an exaggerated stroke of red, the nose a conical red protrusion. The child looked into the Stranger’s eyes, with that strangely melancholic expression that is unique to clowns.

The Stranger put his finger to his lips, communicating silence. Never taking his eyes off the child, he walked back to the horse and mounted. The child watched him as he rode away. The horse walked at a steady pace, and it was only when they had turned round a bend in the stream, and the child disappeared from sight, that the Stranger spurred the horse into a full gallop.

He was concerned that the boy had managed to sneak up on him so, but clowns had that ability, sometimes: to move in deathly silence, to go unseen, to pass upon the flesh of the world without leaving a scar. He rode fast and furious now, not in impatience but with an urgency he did not feel before. This was clown country.

As he rode, the air to either side of him shifted in a kaleidoscopic rush, beats of coloured geometric shapes forming an ever shifting collage of arbitrary patterns which, nevertheless, shaped strange symmetries which ebbed behind as they changed with the horse’s passage. Such vision tunnels occurred from time to time on the Escapement, but could indicate the presence of buried essence nearby. The effect blurred the landscape to either side of him, as though he were viewing it through a colourful prism, but the Stranger ignored the effects as he tracked the scalp hunters, closing the distance between him and them by degree.

At last he came to a gentle rise and slowed the horse, until the effects of the vision tunnel dimmed and at last faded. The land they were in was fertile and bright, with low rolling hills spreading out, and interwoven brooks flowing between them like a network of irrigation canals. Conifers grew on the slopes and around them were bright, colourful flowers, but none of them was the one the Stranger sought.

He heard them even before he saw the smoke of their campsite, for the assassins seemed to feel themselves secure, and they did not bother to hide their fire or lower their voices, and, moreover, seemed to him drunk. The Stranger tied his horse to a tree and proceeded alone, his rifle in his hands.

The assassins’ voices echoed weirdly in between the hills, and the Stranger navigated carefully, listening to the voices as they seemed to vanish and reappear elsewhere without warning; and he realised then why they must have felt so secure.

For this part of the Escapement must have been a maze or, rather, a broken part of one. The manifestation of the vision tunnel should have warned him previous, but he had not anticipated finding one of the old broken mazes, and he wondered how large this fragment could be. He navigated slowly, treading from one hill to the slopes of another, across a brook and past a conifer, which he marked carefully with a knife. And yet when he proceeded he found himself traversing the same patch of ground, or encountering a tree identical or near as made no difference; and the distance to the assassins’ hideaway never varied. Their voices echoed queerly from one end of the maze to the other, but within the transference of voices he thought he began to discern a pattern.

All mazes are ultimately solvable. There is the random mouse approach, and there is wall following, there are the Pledge and the Trémaux. But mazes on the Escapement were not always static, and the unwary traveller using one such method may find that the maze could shift unexpectedly around them. The Stranger, instead, listened for the absences of sound, and it was into their gaps that he directed his steps, ignoring the geography, until the voices coalesced into clearer coherence around him, and their wild seesawing slowed and became recognisable speech, until he was through into the heart of the maze.

A small, derelict mill house of weathered white stone stood on the bank of a gently rolling stream. There were cracks in the stone and moss grew in between the cracks. The wheel of the mill had long since broken into several pieces, which lay sunk in green grass and mud. The Stranger took shelter behind a rock as he watched the hideaway. He was not spotted. A small fire burned by the side of the old mill house, and five men were seated around it, their horses grazing in the nearby grass. The men were laughing. They were passing a bottle around, between them.

They were each as ordinary a denizen of the Escapement as you could find. Two were veterans, or perhaps simple victims, of the war. One had half of a melted clock fused into his abdomen, a black minute hand protruding from his naked flesh like a cockroach’s antenna. The other had living bees trapped in a glass globe embedded in his thigh, and the bees beat angrily against the glass. The man, with a long-practiced motion, would occasionally tap sharply on the glass with the end of his fingernail, momentarily silencing the creatures, who would soon start up again. He seemed comfortable enough in his lot.

The other two were unaffected by materiel. Altogether, they were an ill-kempt, ramshackle group, tied together not by the bonds of human love, and certainly not kindness, but by brutal need to survive. The Stranger noted that the bottle they drank from was clear, and that the liquid inside was a pearly white colour, and he knew that the assassins must have found substance, and had mixed it up with water to create this drink, which was called, colloquially, Sticks. The men, he knew, would be comatose in minutes. They must have felt confident in the security of the broken maze, enough not to even leave a guard. He squatted behind the rock and waited.

The men fell one by one, noiselessly. They lay on their backs, their mouths masticating without sound, their eyes staring unseen at the sky, their limbs twitching occasionally. The bees were silent in the veteran’s thigh. The Stranger was about to rise when someone beat him to it. He saw a shadow detach itself from a hiding place on the opposite hill and begin to journey down. It was a woman, wearing two low-slung pistols on her hips, a wide-brimmed hat which shaded her face, and a large, curved, nasty-looking knife on her thigh, which she unhooked smoothly and held as she descended. She crossed the stream with long, easy strides. On the other side of the bank her head turned, for just a moment, and in the light he saw her face. She wore a black patch over one eye and her other was a deep, calm blue.

She approached the men who were prone on the ground. The Stranger watched the woman rummage unhurriedly through their stuff, upending their bags until she found the brace of clown scalps and this she held for a moment as though considering its worth before she put it back on the ground.

Next she went to the nearest of the lying men and she knelt beside him with the knife in her hand. She cut the man’s throat with one quick, clean motion.

The Stranger watched. The man, with his cut throat, spasmed on the ground, and his legs kicked as though by their own accord, and then he went still. The woman had cut through his carotid artery, with a skill the Stranger could almost admire.

There was a fair amount of blood.

The woman next went to the veteran. The bees in their glass prison beat against the walls but the woman ignored them. She killed the man with the same easy motion. When he died, the materiel in his thigh did not change but the bees sunk with a soft sigh to the floor of their cage and expired.

The third man was different.

Perhaps he had imbibed less than the others, or perhaps what horrors he saw of the other world, with its traffic choked streets and its electric lights and the call of sirens, with its accountants, banks and accruements, the ring of phones, the smell of grease and diesel, had pushed him back to the Escapement, that is to say, to wake. As the one-eyed woman brought her knife to his throat the man’s hand flew up and grasped her wrist with a scream, taking her by surprise. The man, small and wiry, leaped at the one-eyed woman, pushing her off balance. As she fell the man reached for his gun as the woman desperately tried to reach for hers.

A shot was fired.

The sound filled the air before it was snatched away at the edges of the maze, and there is echoed queerly, carried from one path to another. For a moment the two adversaries seemed frozen, as though not sure which of them had been shot. Then the man, slowly, toppled to the ground, half his head missing from the rifle shot.

The woman stood up. Her hands and her face were covered in gore from the killings, but she did not seem to mind. She let go of the knife and her hands rested on the butts of her pistols, but she did not draw. She watched for where the shot had come from.

The Stranger came out from behind his rock. He was holding the rifle. He was not quite aiming it at the woman, but he wasn’t not aiming it, either. The woman watched him. Her single eye was very blue. She did not draw her own guns, but the Stranger assumed she could draw them very quickly if she wanted to. He took a few steps down to the camp. He saw that some of the dead man’s brain had sprayed the wall of the old mill house. The woman watched him calmly. She did not take her gaze off him as he approached.

“They’re mine,” she said.

The Stranger approached. He nodded. He pointed the rifle low, and shot the nearest of the two still-living men. He then went and stood over the other veteran, the one with half a clock embedded in his abdomen.

“Bounty?”

“They’re mine,” the woman repeated.

The Stranger pulled the trigger and shot the man who was fused with the materiel. It was a headshot, like the other.

Now all five men were dead, and he was left alone with the woman.

“Why a knife?” he said.

She shrugged. “Why waste a bullet.”

“How did you get through the maze?”

Her gaze was icy. “I’ve been here before.”

“They killed eleven clowns, three days’ ride from here.”

“They killed a lot more,” she said. “You just shot two of the Thurston Brothers.”

“They were brothers?”

“Only the gimp leg and the first guy you shot. But that’s what they all called themselves, as a gang.”

“It isn’t much of a name.”

“They’re worth two hundred ducats each,” the woman said.

“That much?” He looked at the corpses. “They don’t look worth shit to me.”

“They’re mine,” she said, again, patiently, as though explaining a complex problem to a child.

The Stranger nodded.

“That’s fine,” he said. “I wasn’t after them for their heads.”

“Prospector?”

“Sometimes.”

“I’m Temperanza,” she said. She said it a little expectantly, as though he should know the name.

“Bounty?”

“Aha. Do you mind . . .?”

He shrugged. Temperanza removed her hands from the butts of the pistols and picked her knife up again. The Stranger watched her. She worked efficiently, with quiet confidence, until she had taken the scalps of all the men, or what was left of their scalps. “I really would have preferred it if you hadn’t shot them,” she said.

“Are you complaining?”

“I didn’t need your help, stranger. Don’t flatter yourself.” She sawed off ears where the scalps were too damaged to collect.

The Stranger picked up the bottle of Sticks. Only a tiny bit of dirty-white residue remained at the bottom of the bottle. He tossed it at the mill house wall, where it shattered. As the woman continued in her gristly job, the Stranger added wood to the fire, building up a flame. When the fire was roaring he gently picked up the brace of clown scalps and ears and noses and fed it to the fire.

“That’s that,” he said.

“I could have traded those,” Temperanza said.

“Shoot all the outlaws you want, if you can hit them,” the Stranger said. “But never kill a clown. They do nothing but make people laugh.”

Temperanza looked at him with compassion in her sole blue eye. “No one laughs at clowns,” she said. “No one ever has. They aren’t funny. There’s nothing at all funny about clowns. Unsettling, maybe. Alien, yes. Something other. But they’re not the punchline to any joke I’ve ever heard.”

The Stranger didn’t respond. He watched the flames, and stirred the wood, until he was satisfied that the remains were gone.

“What about the horses?” he said. He didn’t look at Temperanza when he said it, he looked at the flames.

“Yes, well.”

“There are five of them.”

“I can count.”

“Seems only fair I take the horses, if you take the killers’ scalps.”

“What has fair got to do with any of it?” Temperanza said.

He heard her cock her pistol, but he didn’t react. He heard her sigh.

“You take two,” she said, reluctantly.

“I’ll take three of my choosing,” he said. “You take the other two if you want.”

When he looked back at her she had holstered her pistol and was sitting on a rock with a cigarillo between her fingers. She struck a match on the rock and lit up, and blew pungent smoke into the air.

“Not a bad day’s work, really,” she said. “I’ve been following their trail for a while, you know. Since outside of Marxtown, where they hijacked a shipment of substance bound for the rail terminal there. I lost them in a symbol storm somewhere in the Doinklands, and by the time I got out they’d gained a lead on me . . . I finally tracked them here, but by then they’d gone off on a scalping raid. I breached the maze . . . and waited. The only thing I wasn’t counting on was you. Why are you here, stranger?”

“I don’t like bullies,” the Stranger said.

“Who does,” Temperanza said.

“And I am looking for something.”

“We’re all looking for something,” Temperanza said, as though it were the most obvious thing in the world. She drew on her cigarillo, and blew out two perfect rings. The rings floated in the air until they linked with each other, and slowly dissolved in the breeze. “That’s why we’re here, and not in that other place.”

“I’m looking for a flower,” the Stranger said.

Temperanza gestured at the brook and the hills. “There are plenty of flowers here,” she said.

“It is called the Ur-shanabi, and it lies beyond the Mountains of the Moon.”

At this Temperanza’s face grew troubled and she smoked for a few moments without comment. Thick drops of ash collected at her feet, like tiny fungi. Then she said, “I am not familiar with that flower, nor with that particular geographic region.”

“But you have heard of it?”

She shrugged. “Stories. Stories are all we have, really, in this world or the next.”

“What sort of stories?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Don’t ask me.”

“I must,” he said. “I need to know. I have been searching for an awfully long time.”

“Time means nothing, here.”

“That isn’t true.”

“Take the horses,” she said. “I’ll make do with the bounty money alone.”

“Please,” the Stranger said. He knew that she was not quite what she seemed. Temperanza’s frown deepened. She blew out three smoke rings in quick succession. The rings interlocked above the brook and seemed suspended there.

She said, “Long ago, I was on a wagon travelling in the north. It snowed, and the sun went down faster than we expected. The horses were scared, you could smell their fear, and their breath turned to fog in the air. Our breath, too. A storm was coming over the mountains, an ordinary one at first but then we began to catch flashes, pilcrows and octothorpses and trefoil knots . . . the horses whinnied and ran faster, the wagon jostling from side to side. It was then that we began to hear the sound of giant footsteps, of vast and ancient stone pounding the frozen earth.”

“The war.”

“It was only a skirmish, I think now. We never saw the Colossi, only heard them. One of the horses turned into a crow and flew away. My companion’s ear melted like wax. It dripped on the seat. As for my eye–” she touched the eye patch, gently. “Well.

“We came to a stop. Another of the horses had gone so mad with fear that I had to shoot it, out of mercy. We waited out the storm, infinities bursting around us. Then it was all over, and the storm had passed and the battle, it seemed, simply moved away. We’d survived. When the sun rose we saw that the road was littered with materiel, a giant, melted trumpet, a dead lizard with a tiny tree trunk for a tail, bowler hats, a sunflower with a baby’s face. We left the wagon, unhooked the horses and rode on. Shortly after we came to what remained of a farmhouse. There was a well outside, and the skeleton of a donkey beside it. We sought shelter inside the house, from the elements. It was there that we discovered the soldier.

“He wasn’t, by then, much of one. One of his legs had been blown clean off, and the remaining one had turned into a string instrument of some sort, long and delicate, with silver inlays, but it had no strings. The man was drunk on Sticks. He went in and out of lucidity. I think he knew he did not have long for this world, or the next.

“He spoke of many things. It was hard to understand him, and harder enough to care. We grew resentful of his constant babbling. We wished him to die but still he held on. He was a camp follower of sort. He followed the war where it went. And yes. He spoke of one place, with huge figures standing motionless in the sand, and dark mountains, so dark it was as though they sucked the light and made it vanish. But they were far in the distance, I think. These mountains. He was not very clear. Colossi, and some sort of guards at the mouth of a tunnel at the end of the world. I don’t know of any flower.” She jerked her cigarillo into the brook. It hissed when it touched the water.

“No. I lie. He said he wished to smell one, and he used a name. The one, I think, you used. It seemed important to him, as though, if only he could smell it, all will be well. Then he died.”

She shrugged. “It wasn’t a meaningful or noble death, you understand. He passed from here. Whether he lives still in the other place or not, I do not know. We didn’t bury him. The next morning, as soon as the snow had stopped, we continued on our way. Now I avoid the cold, and when a storm comes, I take shelter.”

She was silent then. The Stranger mulled over her words.

“Thank you,” he said at last.

“It’s nothing,” she said. She got up off her rock. She went to the brook and washed her hands and her face from the gore and the blood, as best she could. When she turned back her face had been scrubbed clean.

“Pick your horses,” she said.

•

When the Stranger rode away from that place, the three horses followed him patiently behind. He did not travel fast, and his own horse, retrieved outside the broken maze, which now guarded only the assassins’ corpses, chewed happily on a mouthful of grass. There was a town, Temperanza had told the Stranger before she went, some three or four days ride away, a small outpost, and there he might find a buyer for the horses. The Stranger rode north. Temperanza was heading south, she told him. But directions seldom remained constant on the Escapement. And the Stranger had the feeling he would see her, and her like, again, for all that one did not often see a member of the Major Arcana ride out into the world.

Behind him, the corpses lay undisturbed. Silence settled over the broken maze, to be interrupted again only with the calls of the next unwary traveller to enter it. High in the hills the clowns watched him depart, but what they thought of him there is no way of knowing.

• • •

Copyright © 2016 Lavie Tidhar