It was the first time I entered Albert’s room. The room of the killer. I was afraid. A fear as palpable as the sweat that began to stain my shirt.

I sat on the bed, which was covered with a knit green spread, and looked around me: at the walls covered with that yellowish paper with twisted vegetable images, at the painting of dubious taste depicting a hunting scene in which some bloodhounds gave themselves over to the eternal pursuit of a poor deer, at the lamp with hanging fringe, the heavy curtains, and the closet and night tables that evoked an outmoded style that reminded me of old films from the 70s.

I took a deep breath and it seemed to me that the smell of dust filtered through my lungs until it had reached every cell in my body. Even though everything was clean. As clean as my own room.

Would he be long? Would my voice come out as I had rehearsed?

“I’ve come here for you to kill me, Albert,” I’d say, looking him in the eyes.

And maybe then he’d answer, “I know.”

Or worse, “I have no intention of doing so.”

Would it hurt a lot?

Oh, god. My abstract fear had disappeared to become a physical pain. I had retraced my steps time and again. But even so I had the feeling that my heart was going to fly out of my mouth.

It was warm. There was no air conditioning, not even a sad fan. What a crummy room DeSalvo had.

I got up and moved to the window.

I slid back the curtain and opened the window.

The landscape was different from here but pretty. It looked like a European city. The buildings were crowned by dark slate rooftops and their colored façades were cris-crossed by wooden beams. I looked out at a belltower with a golden clock.

Albert had also had his perfect summer. And it seemed that it had been in Europe.

•

When he’d arrived at the hotel, I was in the outdoor café with Mrs. Wilson. She was having a tea, as usual, and I a Pepsi light.

“Angie, dear,” she told me with that voice like a frightened bird that I can’t forget. “We have a new guest. And he seems young and attractive . . .”

She made a discrete glance toward the reception area and then let it fall again into her porcelain cup. I looked that way with the brazenness that was the trademark of us Americans and which she, a Brit, always reproached me for.

And then I saw him,

Albert DeSalvo.

I recognized him. Some time ago I had had a somewhat eccentric boyfriend who was into those macabre things. And the man who waited at the hotel reception was the same one I had seen in his books about serial killers.

The glass of Pepsi trembled in my hand making the ice cubes clatter noisily.

Mrs. Wilson lifted her cup of tea to her lips and then realized that something strange was happening to me.

She opened her mouth to tell me something, but she didn’t manage to utter a word.

“Granma!,” her granddaughter interrupted us.

Little Susan was four years old. She was a lovely child. Blonde, and as pale and English as her grandmother.

“Grandma,” she repeated. “Come and see what I’ve made, a sandcastle! It’s biiiig!”

“Then it would be a fortress,” Mrs. Wilson answered with that smile that sometimes seemed to me to be the sweetest in the world. “Come and show me, dear . . . You’ll excuse me, Angie?”

And without waiting for my response she stood up. She took her parasol, gave her hand to her granddaughter, and wandered off among the garden’s bushes heading toward their beach.

So I couldn’t tell her.

“I know him!!” I could have shouted. “He’s a murderer! The Strangler of Boston! He killed over ten women. He’s a serial killer. That man is a rapist and a killer! You couldn’t know, but I do . . .”

But Ann Mary couldn’t hear me. She’d left for her beach with little Sue.

I watched her draw away, wearing her dress of lace and embroidery, holding her granddaughter’s hand. And I didn’t say anything.

And Albert murdered Mrs. Wilson.

And like a shadow her granddaughter disappeared with her.

It was a shame.

Ann Mary had showed me how to play bridge and I enjoyed chatting with her in the outdoor café. I enjoyed her way of speaking, so outdated, and her incisive comments sharp with irony.

I liked to share her moments; when Ann Mary taught French songs to her granddaughter, or told Sue stories or made them up. The two of them were happy together. Very happy.

For them, their perfect summer had ended.

•

I kept the secret. I didn’t tell anyone what I knew.

I avoided encountering the murder and fortunately that wasn’t difficult for me. He was an early riser and I wasn’t. I went down to breakfast at nearly ten thirty, just before it closed. And he must have done so when they first began to serve breakfasts.

I never ate at the hotel, I did so on my beach with the group, because the surfing school I had signed up with that summer always organized a barbecue beside the sea.

In the afternoons, I stopped visiting the indoor or outdoor cafés. And at night I never passed through the hotel’s bar or restaurant. If I was hungry, I ordered something from room service.

Almost every day was spent entirely on the beach with my people.

•

DeSalvo, the strangler, only saw me once. Out paths crossed at reception. He gave me a long look. I lowered my eyes and quickened my pace as much as I could. I don’t think I was his type.

That summer I was twenty five years old. I had signed up for the surf school and I spent all day with a neoprene suit or those long t-shirts that were in vogue then. My hair was very short, shorter than many boys, and I was muscular and strong. I spent my days out in the air, enjoying the waves and the sea, and I was tan.

No, it seems I wasn’t his type. I think that I must’ve seemed too mannish for him. Perhaps even a bit threatening.

•

After Ann Mary’s murder came that of Laura. She was a Spanish woman who spent the summer at the hotel with her husband and two little children. They were noisy but nice. They breakfasted as late as I did, and at night they stayed up all hours playing cards at the hotel’s outdoor café. They were from the 70s. With those shirts with those regrettable collars and psychedelic patterns.

When Laura disappeared, so did her family.

•

And then was Julie, the newlywed. And with her, her husband also evaporated. Although, honestly, I didn’t mind having that pair of sickly lovebirds gone from my sight.

•

And then it was Petra, the German woman. And then Elisa, and Clara, and Berta, and Denise . . . And when someone left, a new guest arrived at the hotel. Each one clinging to their own perfect summer . . .

•

Oh. And then came a time when I no longer knew if the woman disappeared on their own or because Albert killed them.

Although to be a purist, I don’t know if I should say killed, because after all we were all already dead, right?

•

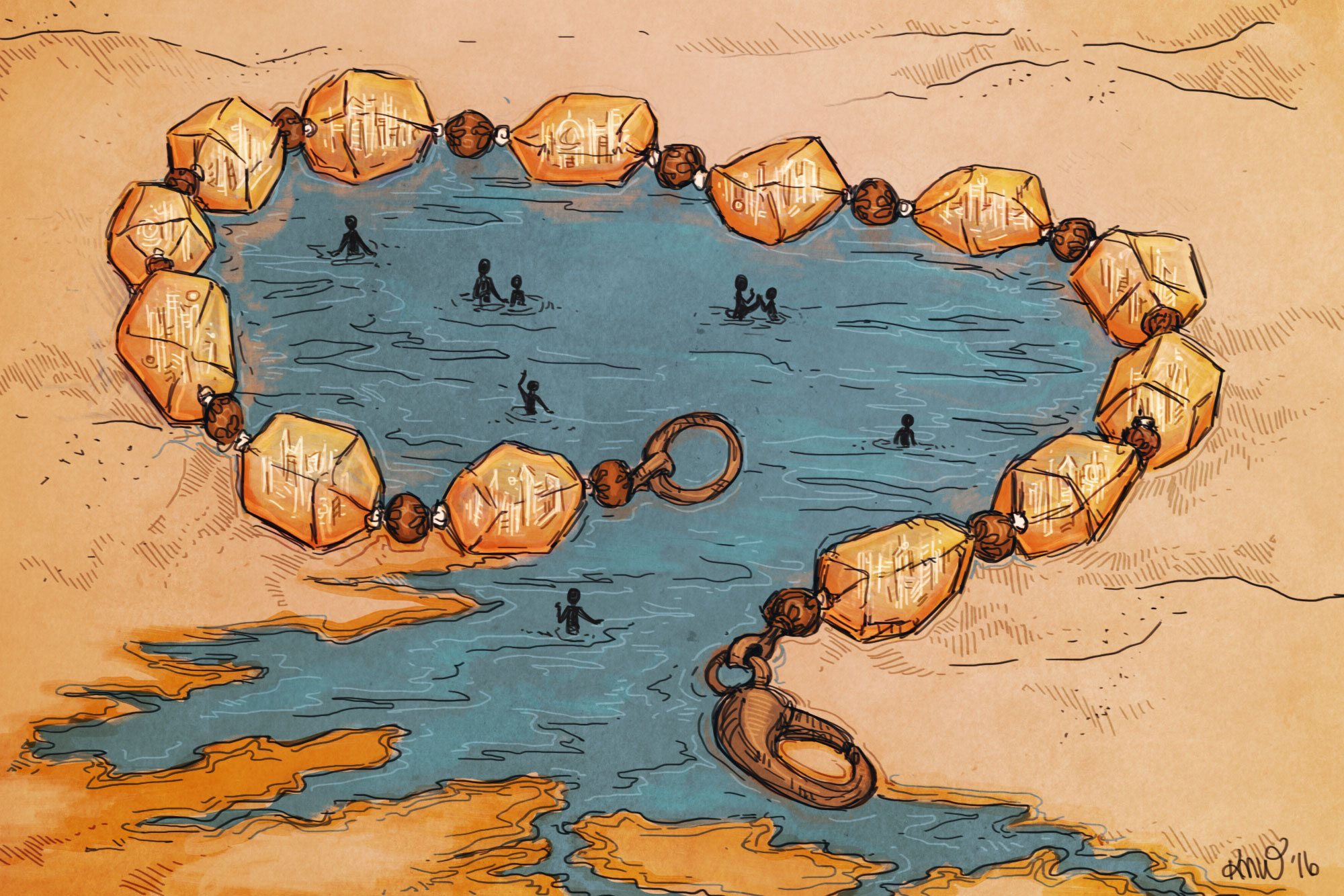

Many years after that summer, when I was a mature woman, my daughter gave me an amber collar as a gift. One of its beads, the largest, had an insect inside it. A poor creature trapped in resin and fossilized for all time. Just like all of us prisoners of our shared summers in a hotel beached in a space without time.

•

My perfect summer was that of 91.

After breaking up with Daniel I signed up for a surfing academy. It had just occurred to me out of the blue. To do something different. To forget him. Just fifteen days during which I surrounded myself with strangers who almost wound up becoming a part of my own family.

That summer I met Alice, Peter and Richard . . . We spent all day on the beach, first trying to keep our balance on the waves, then perfecting a style which over the years I’d be proud of.

We ate beside the sea, making barbeques day and night, singing beneath the stars, we revealed our secrets to one another with the trust that strangers have . . . That was my summer. The happiest of my life.

And when I died years later, I returned without knowing why to my perfect summer.

•

Like Ann Mary. She told me she had never been as happy as when she had summered with her granddaughter in 1933. Yes, there would later be other summers and other trips with Sue, but none were as brilliant as that one . . .

•

It’s as if those moments that were so happy and full had become engraved in fire on our memories, so that when we died we were unable to escape from them and we found ourselves chained to our perfect summers forever. Condemned to relive them . . .. Or blessed to relive them, depending on how you looked at it, of course.

•

Because I was young again, and laughed with the force of those who don’t know the fragility and volatility of life. Because I had with me that California sun, and the salty taste of Richard’s tender body.

Yes, the summer of 91 was perfect.

I remained trapped in it.

Just like the insect in the amber of my necklace.

•

The hotel had no name. And its architecture moved through all the styles that splattered the twentieth century.

The entrance staircase was flanked with art decó iron gates carved with labyrinthine vegetable motifs. The reception area breathed a functional rationalist that contrasted with the restaurant which was decked out in the happy pop colors of the 70s and the outdoor café of heavy iron furniture from the beginning of the century.

Some efficient, discrete, and silent employees were in charge of making our stay comfortable, offering us everything we could need.

•

At first, on reaching the hotel, we were all a bit confused.

We asked ourselves what we were doing there, and where were we, but then, intoxicated by the magic of the place, when we understood that we would repeat forever out happiest summer, we stopped worrying. And little by little, we let ourselves be carried away by our routines and the viscous perfection of every magnificent day.

Until Albert DeSalvo arrived, clutching his own perfect summer.

•

And then came a brilliant summer day, which seemed just like all the others, and I realized that I was the guest who’d been in the hotel the longest. And that I was no longer in the mood for the company of Alice, Peter and Richard as I was at the beginning. The barbeques and the group’s constant laughter bored me, they suddenly seemed to me to be too young and much less interesting than Ann Mary, who I missed more and more.

•

That’s why, the day I discovered on waking that I had no desire to wake up, I went in search of the murderer.

•

Night had fallen and Albert didn’t return to his room. The fresh air of his European night began to feel uncomfortable for me.

I stopped up to close the window.

The city was already wrapped in shadows.

I wrapped myself in the knit spread. Some distant thunder announced a storm.

My heart had quieted some time ago. I no longer felt afraid. I only felt exhausted.

It must be very late.

I breathed a new air that seemed to carry on it the scent of wet earth.

I was tired of waiting for him.

•

I carefully folded the spread. I closed his door silently, and headed toward my room.

I crossed the hallway in darkness and felt myself watched by the frozen glances of the portraits that dotted the hallway. Serene realist faces, and delirious expressionist and abstract ones that contemplated me as I struggled not to shed a tear. I felt like them, condemned by an artist who had sentenced them to show the same expression for all eternity.

Dragging my feet, I climbed the spiral staircase toward the top floor.

My room was at the end of the hallway.

I was surprised to see a tongue of light escape from under the door.

I opened it slowly.

Albert was waiting for me, seated on my functional bed from the end of the century.

I smiled at him with my eyes still shining.

“You’re not going to believe this, but I’ve spent all day waiting for you. In your room.”

“I was waiting for you, Angie.”

I let myself fall beside him, exhausted.

“Will you hurt me?”

He shook his head no.

I had never seen him so close. He had very dark eyes and seemed sincere. That summer he must have been as young as I was.

“I want to escape from my perfect summer.”

“I know.”

“Don’t hurt me,” I begged with a whisper.

“Don’t worry.” His voice was sweet, even a bit fragile.

I closed my eyes.

•

I breathed the air of that final night of summer. It smelled of sea, salt, wet earth. It tasted of young Richard’s skin. It sounded like waves breaking on the shore and the distant laughter of the group on the beach. It was the growling heat of midday and the fresh nighttime breeze; it was the taste of the meat on the barbeque and of the chilled Pepsis. It was Richard’s warm skin and his hair covered in sand.

•

It was the end of my perfect summer.

• • •

Copyright © 2016 Susana Vallejo , Lawrence Schimel.