“Yes.” A pause. “Yes. I understand.” Julianne found the page in her business notes for the ex-husband on the phone. She remembered him now, more clearly than she had from the disembodied voice on the other end of the line. Not too handsome for the woman he’d been with, when they’d been married, but definitely too young for her—which was why they had come to the Norwich IVF clinic in the first place. To save a few embryos for later, when they would “find time.” They’d never found it, and now they never would—they were getting a divorce, and the embryos needed to be held in custody. She doodled in the margins near her old notes on him—brown hair, straight nose, stock broker, slick talker, PBIB (which was her code for probably bad in bed, though she’d never admit it, not even under oath)—as he threatened legal action for any unauthorized implantation. She knew later on today there would doubtless be another call from his soon-to-be-ex wife. Dyed hair, collagen enlarged lips, botox, and a ring, which Julianne-of-the-past had sketched out while seeming to pay attention, the kind of pyramidal monstrosity which had been en vogue a decade ago, and probably pre-dated their relationship.

“Don’t worry. We won’t be touching your genetic materials, Mr. Miller, until we hear firmly from your lawyer.” Genetic material was less emotionally charged than embryo. Things could happen to embryos. You could watch the Discovery Channel and find them, watch cells dividing, see small suckling baby kangaroos. But “genetic materials” were the sorts of things you rinsed off in the shower or threw out with the trash.

“Yes,” she continued. “I look forward to hearing from your lawyer.” And getting a letter in triplicate, with signatures on all the lines. “Norwich clinic wishes you the best in this difficult time.”

Julianne hung up the phone and put a “Sign Here” sticker-tab onto their page of her notebook. When the next lawyer called up, she would put him on hold to pretend to find her notes, but she would really be walking down the hall to purchase a Diet Coke from the vending machine. Diet Cokes did wonders for her attitude towards customer service. And she felt it humanized her for incoming new clients, the ones that she would smile at as she passed the waiting room, as they held hands slick with nervous sweat.

She cracked open a Diet Coke, and then went through her appointments for today. Billing reconciliation in the morning, and then new clients in the afternoon. Julianne wasn’t a doctor. She was more of an office manager. New clients saw her first, and she screened out the crazies or the merely poor, before passing them up the line. And she made calls on the clients of the past. If people wanted to keep their embryos on ice for an indeterminate amount of time, they were going to have to pay an indeterminate amount of cash, and sometimes they forgot that. It was her job to gently remind them, before the collection agency did. Julianne was Norwich’s public face, bridging the gap between doctors, the accountants, and the clients.

Prior to this she’d worked much the same job in a plastic surgery facility, before she felt she’d gotten too old. She possessed neither children, nor a willingness to have any. She emailed the “hold” order on Mr. Miller’s half-embryos to the cryolab.

She was thirty-two.

•

“When did you know about this?”

Richard knocked at her doorframe, with a paper print out in hand. It was as archaic as her notebooks. He was new, dark-haired, dashing. Seeing him, she felt a deep squeeze of interest.

“About what?”

He walked in and settled himself into her chair. He could have helped himself to her Diet Coke, if he’d wanted.

“The hold order—we lost those embryos last week.”

“Lost?” She tucked a lock of hair behind her ear and leaned forward. Coquettish wasn’t in her vocabulary, but cleavage was.

“Yeah.” He glanced at the paper again. He was nervous. It was unlike the lab techs to ever be nervous. “We were waiting until our month end reconciliation to let you know.”

“Can you define lost?” She drew a circle in the air to indicate the missing cells.

“It happened during the fire alarm last week. Someone must have bumped the Zero Gee on their way out and broken a straw.” The embryos were stored in thin glass pipettes, carried up from Petri dishes into their new homes by the power of capillary action.

“Heh.” Julianne rocked back in her chair. She remembered the alarm and the evacuation to the parking lot. The chances of Mr. Miller and Mrs. Not-Miller’s divorce ever coming to a legal conclusion and a subsequent implantation were slim to none. Which was good because right now the last fruit of their combined loins was frozen to the inside of a Yosan ZG Tempurchill.

“You’re not angry?” Richard asked.

Julianne’s lips quirked up. “They’re not my eggs.” The contracts she managed had clauses that covered the clinic in these situations. Fires, tornados, floods—all bets were off on embryo storage when it came to acts of God. You could only be held accountable for so much. “Did someone get the name of the fire chief?”

Richard nodded and stood quickly as though a visible weight had been lifted from him. Julianne watched him—more specifically, his ass—as he walked out of her room.

“Richard?” she called after him. “Was there really a fire?”

He turned, framed beautifully by the white paint of her door frame, and the cool blue pastel of her office like a precise mat cut beyond. “That’s the strange thing. No.”

•

“You’re just not sure yet.” It was a statement Julianne was unafraid to make. Few people came in with their minds made up, even the ones who thought they knew what they wanted.

For the men it was easy, a little time in a private room with a sterile cup. For the women, there was timing and shots, hormones and bloating, and at the end, a small operative procedure. Julianne sat across from this couple with a calming smile, while the wife slowly flipped through the same brochure for the second time. Even the ones who knew that they wanted children more than anything else in the world, who had read all the information available on the internet, gone to open lectures, or listened to friends—there was still a personal calculus to be done, of certainty versus doubt. The only ones that came in already sure of their answers were Catholics or knew they had an ovary that needed to come out.

“What happens if we go through with things, but then decide we don’t want it?” the woman asked.

“If you don’t want to immediately proceed with implantation, we’ll continue holding your embryos for a nominal fee. If you decide not to ever implant, you may donate your genetic materials to science, a willing donor, or they can be destroyed.” Julianne set her pen down and bridged her hands like a minister. “We’re not here to rush you. I can set up an appointment with our doctor for you tomorrow, next week, next month. Or you can call in when you feel that your time is right.”

“Waiting for the right time is what got us into this mess,” the husband said, leaning over to squeeze his wife’s knee. She shot him a dark look in return.

“We’ll be calling,” she said, standing, decided.

“Please do.” Julianne stood as well and closed her notebook before they could see her notes with a caricature on them—white, middle class, dull—and handed them the clinic’s card, out of the silver card holder on her desk. “Any time.”

“Thank you.” The wife gave her a cramped smile and collected her husband to leave as though he were on a leash.

No sooner had they left through her door, the ringing sound of the fire alarm began, like a metallic cicada cry. She decided to go out, not after the clients in the direction that the nearest exit maps pointed her, but to go towards the vending machines and laboratories instead. She found a dollar fifty in her top desk drawer and slowly made her way to the back.

She felt more than heard the heavy thump of the laboratory door sealing shut, and saw its keypad blinking red from the corner of her eye. She purchased two sodas and walked down the hall towards the vendor loading dock, where Yosans and Diet Cokes were delivered alike. She opened up one soda and—she thought she saw someone in the laboratory. Julianne stepped back and peered through the slat of wire-meshed glass set into its door. No one could be seen—but she couldn’t see the entire laboratory, there were partitions and machinery in the way. She watched and waited as the sputtered beginnings of her Diet Coke frothed out and dried on the back of her hand. Who else would still be inside? She frowned into the now-empty lab. If she didn’t go outside soon someone would come in for her. She stared in for as long as she could, until she convinced herself that she’d seen nothing but a shadow, or a close-up lock of hair, and then walked out to Norwich’s designated meeting zone to be present and accounted for.

After that came the waiting. Julianne made her way over towards Richard, and offered him the extra drink. “The machine gave me two,” she said as he took it.

“Thanks.” He opened it, with a hissing pop, and shook his hair out of his face before taking a sip.

“Everyone’s out here, right?” She could account for all the office personnel and doctors. He glanced over her shoulder and tallied up the rest of the laboratory techs.

“Each and every one. I just hope no one bumped anything on their way out this time.”

Julianne grinned. “As long as it’s during a fire alarm, it’s an act of God, and we’re covered.”

Richard smiled back. “Well that’s ironic.”

“Quite.” She took another long drag of soda, and wished it were something sexier to drink, maybe slightly alcoholic. She realized compared to who else was out there in the parking lot with her though, in her competent public professional garb and minus a lab coat, she was holding her own, quite well.

“After this—after work—would you like to go out with me?” Richard asked.

Her lips grinned around the metal edge of the can that she was still drinking from. She released it like a parting kiss, leaving a stain of ruby frost behind. “I would love to.”

He smiled and behind him the alarm stopped.

•

She slept with him that night. He was glorious and firm, and she was soft and yielding. The next day, after they’d taken separate cars to the same place, she went into her office, scanned her appointments, and took out her personal notebooks from her locked fire safe.

She found the last page, where she was going to write today’s date, when she found the margin already occupied.

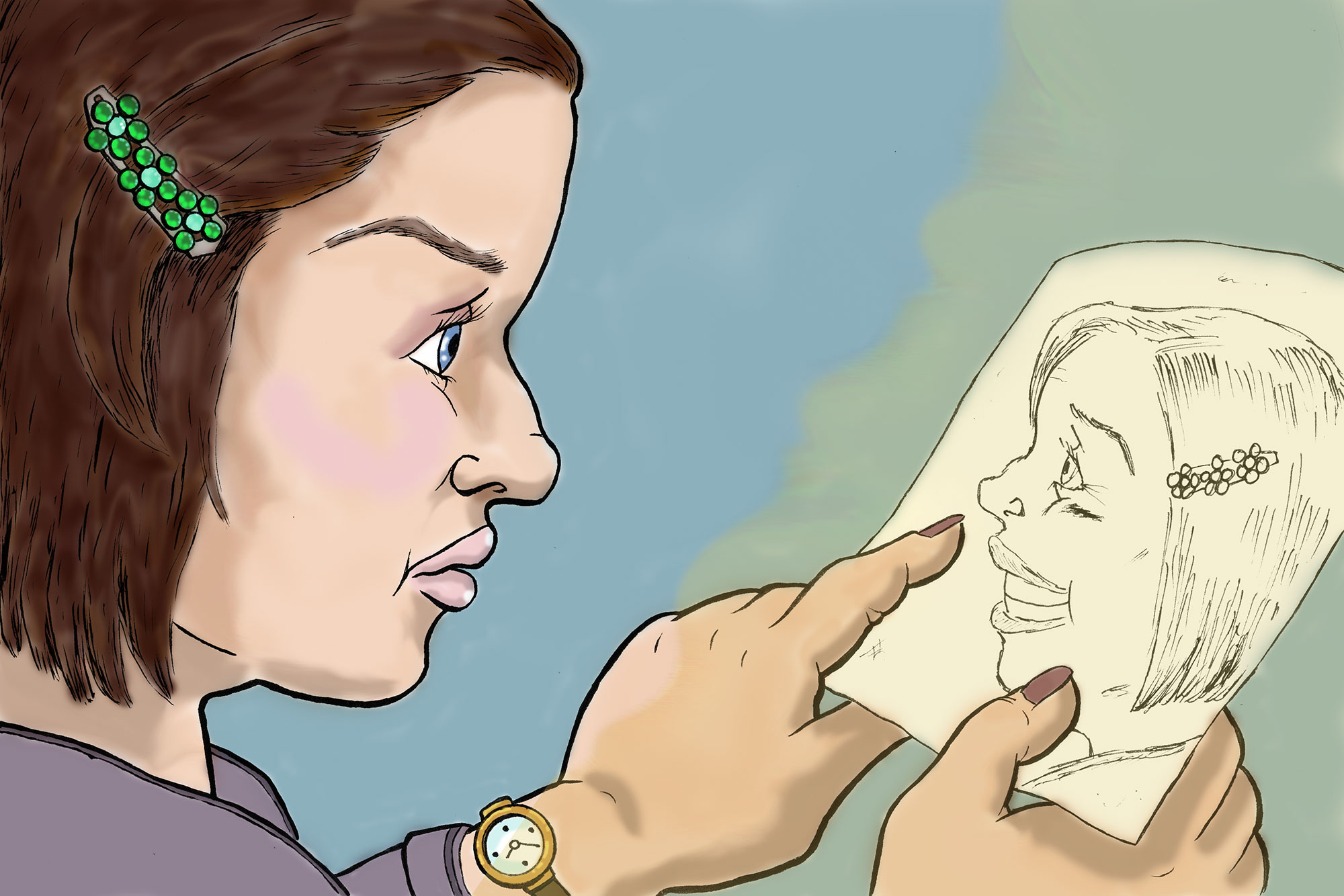

A drawing of herself. A little older, perhaps—or the cartoonist had been in a rush, and had smudged the shading of the pencil underneath her smile. When was the last time she’d smiled? Last night, yes, but before that? She traced her fingertip over the drawing of herself like it was a hieroglyph she was unable to comprehend.

Julianne opened the fire safe again, and found all of her notebooks in order, safe. She closed the door and repeated the procedure, as if a magician’s trick might be performed to change what she saw there. She took the notebooks out, and thumbed through them, and found a new Sign Here tab, one she didn’t recall placing. The entry was less than three years old—she opened the notebook out on her desk, and saw in the margins an entry in handwriting she recognized as hers, but that she did not ever remember writing down. “Trust me,” it said, near Mr. and Mrs. Brezner’s name.

She turned on her computer and went through the database. They verified contact information every five years—it would require too much effort to do it sooner, and the clients had an obligation, which they’d noted and signed, to keep the center abreast of any changes made earlier than that. Before she could convince herself otherwise, she dialed the last known number, and asked for Mrs. Brezner.

“Who is this?” asked the male voice that answered the line.

“Julianne Carter, from the Norwich IVF clinic.”

“Oh.” There was a long pause. “I suppose we should have told you.” Another pause. “She died three months ago.”

Julianne swallowed. “I’m so sorry for your loss—”

Mr. Brezner cut her off. “You can donate them. To science. Sarah would have wanted that. She was a teacher.”

“I’ll mail you a form to sign then, to that effect. When we receive it, I’ll see to it that we refund your last three months freezing fee.”

“That’s very kind of you,” Mr. Brezner said, in rushed tones, and hung up.

Julianne tore out the page that had her face on it and put it in the shredding bin.

•

She couldn’t remember giving anyone else the code to her fire safe, ever. The notes there were her personal files—she’d run them through the shredder personally if she ever left this job. Had someone seen her unlock it? It was behind her desk, and to the side—she tended to block it from view with her body, when she bent down in her chair to get inside. Was there a camera somewhere in the room? She stood, closed the door, and carefully checked her shelves full of medical journals that she’d never bothered to read, and turned each of the carefully selected calming knick-knacks beside them around, looking for a lens, leaving them backwards or on their opposite side, just in case.

It seemed like a horrible joke. But one that only she could have played on herself.

•

The fire alarm went off again with gusto at two in the afternoon. Julianne waited and went by the soda machine, pretending to push buttons until the last lab tech had left. As soon as the door fell shut and the hall was empty, she strode down and peered in through the window. This time she saw someone. She knew it. They had dark hair, streaked with gray, and they were leaning over one of the Yosan Tempurchills, opening it up wide.

“Hey!” Julianne beat on the door. The alarm continued, making it impossible to hear her own voice. The person inside the lab looked up at her.

It was her. An older her, slightly heavier, but the face was the same—the eyes were the same.

Her double smiled.

Julianne reeled back from the window.

Between rings of the alarm, she heard the first syllable of her name. “Jul—” Richard peered in from the doorway to the loading dock. She could see his mouth moving as he tried to shout over the next ring. She looked back at herself, being industrious inside the freeze room, before running towards him, down the hall.

“What is it? You look like you’ve seen a ghost,” he asked, escorting her down the dock and into the bright outdoors. His hand found the small of her back, offering appropriate aid for her heels on the cement downgrade. The thrill of illicit work contact gave her another chill.

She opened her mouth to tell him, and realized how crazy she would sound if she did. She pouted instead. “It ate my quarters.”

He laughed. “I’ll buy you another drink tonight then. If you’ll let me, that is,” he added, looking down at her.

From her angle, looking up at him, his face seemed haloed by the sun. “I will,” she said and smiled.

•

“What do you think about children?” she asked, rolling over on her stomach.

They’d had a brief conversation, mutters really, before he penetrated her for the first time. She had an IUD in, but they both agreed condoms please, because you could never be too redundant, not where genetic materials were concerned.

“Other peoples’ are cute, I suppose.” It was Saturday, and Richard had stayed over. She was surprisingly unselfconscious around him. Perhaps knowing what she’d look like in twenty years helped.

“Do you want them? One? It?” she asked.

He rocked up on his side, to balance himself on a bent arm. “Someday. Probably. Maybe,” he said, with her exact inflection of uncertainty.

“Don’t make fun of me,” she said.

“I’m not. I honestly don’t know,” he said, and she knew he wasn’t lying.

There was a silence between them that Julianne’s mind went roving in. She thought that married couples, who indeed had children, maybe missed their chances to be pensive, listening to a quiet that let them think too long and imagine too much. Her mind ran the differences between the her of the now, and the her of the future, potential births, sleeplessness, teethings, graduations, heartbreak, pain.

“What happens to the old ones?” she asked, breaking the still.

“The old what?”

“The embryos. The genetic material. I forgot to forward a work order—a woman died and her husband wants to donate them to science.”

“A few days still frozen won’t hurt them then. We can send them off for stem cell research at another facility.”

“And what if there’s no science involved?”

“Then they can be donated to one of those snowflakes groups, so that sterile republican men can appear to thwart genetic destiny.” He shrugged. “Or if the lease lapses, we set them out on the counter top for a day or two. The cells desiccate and we throw them away.” Richard looked down at her, and reached out to stroke her brow. “You already know all this, Julianne.”

“What do you think about that?” she pressed. “Do they die? Can they die?”

“I’m Jewish.” He laid down and braided his fingers together across his chest. “We believe that a fetus isn’t its own human until it’s half out of its mother’s body, technically.”

Julianne lay there beside him, thinking about having life pulse inside of her, thrashing around, searching blindly for a way out. “That’s quite civilized.”

He spread his arms wide on the bed they shared. “On behalf of my people, thank you.”

•

Monday morning, Julianne found her open notebook on her desk.

She stood in the doorway, transfixed, knowing that she had not left it out while at the same time praying that she had because to consider any other option courted betrayal—or lunacy. She walked over slowly, like a woman condemned, and flipped to the last page.

There, in her own handwriting, was written: “We need the new code.” And beneath, a small sketch of Richard, aged exactly as the one of her had been prior.

Had she even known the old door code? She tried to think—yes. It was a day off from her birthday, and a doctor had told it to her once, so that she could deliver a private message to the technicians inside. Julianne stared at the notebook, swallowed dryly, and wished for a Diet Coke.

The drawing of her, of him, and seeing some other version of herself—everything was pointing toward one conclusion like the tip of a pipette.

She wrote in the notebook without sitting down. What’s going on? and underlined it firmly. Then she walked away. If it was her, she’d know she’d done this. She would know that she would know. She went to the bathroom and waited—for herself.

No one came. Not one of the receptionists, or the executive doctor’s secretary. She sat on the velvet ottoman that wasn’t quite a couch, looking around at all the fancy marble and wondering who it was truly for, when a woman walked in.

“Are . . .you . . .” Julianne began, spacing out the words, not sure what she was asking.

“Nervous?” the woman finished, with a short laugh. “Yeah.”

A client. Julianne sank back into habit and gave her a warm smile, the kind her old plastic surgeon bosses had wanted to freeze for fear of wrinkling. “Don’t worry. It’ll be fine,” she said, and stood to walk back.

Which would be more satisfying? Another sign, or the lack of one? Her notebook was where she’d left it, she could see it from the door—the fire alarm wailed again.

The sound propelled her forward, and her own handwriting greeted her beneath the sketch of Richard: “Eugenic war. Time travel. Direct overlap bad. Time short. Trust me. Trust you. Trust him.”

Julianne stared. Somehow she had written this.

Some when.

Richard came by and shouted, “I came by to personally escort you to safety!” She couldn’t hear him over the alarm, but she could infer it by the extravagant bow that followed, encouraging her to join him in the hallway. His elegant dating exterior was flaking off due to too many contented orgasms and he was showing his true nature, corny underside and all. Oddly, she found it charming. Trustworthy, even. She didn’t need to read the note.

“I have something to show you,” she shouted into his ear. She left her notebook behind, and before she could question herself—now, or then, either one—she pulled him down the hall. She would know again—she had too.

She stopped in front of the cryogenic room’s door, with its window’s narrow slat. She was there again, on the inside, waiting because she knew. Julianne waved at herself, and the other her, the her of some distant tomorrow, waved back, her face now lined with wrinkles and her smile still truly warm.

Julianne of the now looked up to Richard, whose mouth was hanging open.

“That’s—”

“I’ll explain what I can.” Julianne yelled into his ear, pulling him down the hallway. “Come on.”

•

“Turns out it’s a system flaw. When the water pressure drops, the alarms go off.”

Had she known that before? Did she learn that in the future? Was she learning it, or re-learning it, now?

Richard sat inside her office across from her. He’d spoken with the fire chief moments before the all clear.

“So that explains that,” he continued like a scientist, putting what he could into boxes, until he couldn’t anymore. “But what explains—”

Julianne unlocked her fire safe and pulled out her notebook. She flipped to the last page she’d left herself, where the same note still sat, with an addendum. “All will be well.”

She pulled all of her notebooks forward, and saw that where the papers had been facing the back of the safe, there were fifty or so scattered Sign Here notes. She decided to show him the last note, first.

Richard stared at it. “And you’re sure you didn’t do this?”

“Actually I think I did. Only—not this me,” she said, pointing at herself. “Some future me.” She watched his face while she said it. He was the one in the client’s chair, but it was her turn to be nervous. She bit the inside of her lip while she waited for him to speak.

Under her attention, Richard gave a nervous laugh. “Sorry. It’s a bit much to take in.”

“You saw her too, you know.” Julianne said, and then blurted out. “She needs the new door code.”

Richard shook his head. “There is no new door code, Julianne.”

“Oh.” Her stomach sank.

He leaned forward, to read the note, upside down and backwards again, then slumped backwards. She’d seen clients look just like him before in that chair, worried and afraid. “She needs the code. Not the door code.” He pursed his lips and measured her across her desk. Measured them, perhaps, the way they fit together when they were fucking one another in bed, the way she made him laugh in a coffee shop before a movie, all the things they’d done and what, if anything, was yet to come. “We’re getting a new Yosan in. It’s to hold all the old straws that we can’t afford to store singly anymore.”

Julianne’s throat tightened. “The ones that no one wants. The snowflakes.”

“The ones who won’t mess up the timeline.” He stared off into the space above her left shoulder. “They must have great transfer ratios in the future.”

“Or they’re just that desperate. She said it was a war.” Julianne reached into the safe behind her and pulled out the other notebooks. She turned them towards him, paper-side out, so he could see all of the yellow tabs. He reached forward and ruffled them without opening the books, like he was petting a yellow-striped cat.

“You’ve been chosen, Julianne.”

Julianne thought of all the work her future self had assigned for her. “I told myself all will be well.” She looked up at him. “I hope I’m right.”

•

Julianne spent the next three days tracing down leads on each tabbed couple’s death, divorce, or disappearance. She claimed to be going through old files, and the accounting department was pleased that she was helping them clear their rolls of people whose genetic material they were obliged to keep hold of, even though the original owners had long ago lost track or stopped caring.

She saw little of Richard during this time. There were glances at each other in the halls and distant acknowledging nods, but no contact. She found that the pillow on his side of the bed still smelled like him, and so she changed the pillowcase, but didn’t wash it just yet.

She didn’t call him either. Normally she didn’t approve of playing games—she was up front with her wants and desires, and it had lost her men before—but this was his decision to make, without any further input from her. She just continued to work, clearing old paperwork, enrolling new clients with a passion, imagining their children at some distance in the future, their unused embryos unfurling, unfolding, like cellular flowers, multiplying and dividing. She went to work with an enthusiasm she had heretofore lacked, and in dealing with her new clients, it was contagious. Doctors discussed signing bonuses. The accountants suggested she get a raise.

There were no more fire alarms now that the solution had been found. And the Mega Yosan was installed seamlessly—she peeked out when she heard the commotion in the hall, the large freezer being wedged into their cryoroom, the lab techs dancing around it like it was a pagan god.

It would take them a few days to bring it online and sort out its straws. She couldn’t resist peeking in the room every time she bought a soda, and Richard caught her doing it once. He shook his head at her—but he smiled.

•

“This is it.”

It’d been a week since she’d heard from him last. His smile was all she’d had to hold onto, his smile, and her faith.

When he came into her office she hadn’t finished researching all of the tabs but she’d made a considerable dent.

“How will it work?” he asked her, as she took the folded piece of paper from his hands.

“I don’t know. I don’t know now. I will then, I suppose.”

As soon as she opened the paper and read it, she’d know what she needed to know. She felt along the folded edge, then opened it up, and read the code.

She expected a miracle. Bright light, harp music, the distant fluttering of wings. What she got was twelve digits. She read it three times and tried to commit it to memory.

“Do you feel different?” he asked, leaning forward in the client chair, his elbows on his knees, hands clenched together in one penitent fist.

“No.” Julianne set the paper in her shredder bin and met his eyes. “Do you?”

He reached out one hand, set it on hers, and squeezed it gently. “No. Not at all.”

• • •

Copyright © 2017 Cassie Alexander