Hardee’s is right across the street from the graveyard. So, while you’re leisurely sucking down a hand-dipped vanilla milkshake, trying to figure out exactly how one would hand-dip a milkshake, you’re interrupted by the view.

It’s not a very peaceful looking resting place. The only thing separating the dead from asphalt is this tilting iron fence. The poor crippled thing, it never quite recovered from that run-in with the Ford F150. And I don’t know who’s in charge of the real estate, but there doesn’t really seem to be any rhyme or reason to the spacing of the graves. Everybody’s just crammed in there like factory farm cattle.

The trees are the same way. The malnourished water oaks are all dark and twisty from years of light scrounging. Spanish moss, the botanical Rapunzel of the South, lets down scraggly grey tendrils that just brushes the tops of the gravestones.

Sometimes I think I should go wipe off the headstones; Spanish moss is crawling with chiggers. But I don’t really know any of the residents personally, so that could get awkward. Especially if I ran into a visiting widow or something. I mean, how would you feel if you were a grieving widow and you saw some eighteen-year-old chick poking around your husband’s grave? Not cool.

“Izzy,” Aunt Amelia says, following my eyes. “If you have me buried there, I will haunt you. Hard.”

“But aren’t all your peeps over there?” I squint my left eye, scanning the tombstones until I find the Dawson cluster. I point with my whole arm and straw.

She plucks the straw from my hand and slips it back into my shake. “Exactly.”

“Alright, Viking send-off it is. Fire and flames. Anyway, you’ll probably outlive us all.”

•

“The neighborhood’s going to hell.” Aunt Am can’t get through a walk without saying it at least once.

Cerberus is banging into the fence again. I really think he could jump it if he wanted to, but he doesn’t think so, and that’s what matters. He just rushes it and slams his thick body against the chain link fence. Over and over again. The definition of insanity.

His name isn’t really Cerberus. I don’t really know what his name is; I’ve never talked to his owners. We just call him that because when he comes at you, it actually sounds like a pack of wild dogs. He’s somehow able to bark, snort, and growl all at once.

It makes Artemis nervous. Artemis is Aunt Am’s greyhound. She always has at least one, rescues from the Track. Most of them she fosters for a little bit and then finds them homes, but Artemis is for keeps. Like me.

“I can’t even walk Art in peace anymore,” she continues.

“Yeah, he’s a pain in the butt.” I pick up the pace a little bit, moving to the other side of the dirt road. There’s no house there, just an empty lot. The Magnolias are crushed in close together, with leaves that slowly change color, like when I let the lady at Dazzles ombre my hair. Closer to the ground, in the shadows, the leaves are a deep blackish green, gradually lightening as you move up to the tree closer to the sun, and big white flowers crowning the top. They’re supposed to smell really good, but I can never reach one to sniff it. A hot, sticky burst of wind throws the leaves and branches into a shiny emerald mosh pit.

“And the yard. Seriously, there’s an engine on his porch. An engine.”

“Mm-hm.” A butterfly, a Zebra Longwing, visits the Magnolia assembly.

“It’s a mess. People just don’t care.” Aunt Amelia sighs. I feel bad for her. She’s lived here her whole life, before the neighborhood was even here really. Her daddy built the house when there was nothing but azaleas and ticks living in Woodson Park. Before there even was a Woodson Park. Just woods. I think she sees herself as the queen of the neighborhood, and she’s getting more and more frustrated with her subjects.

I try to make her feel better. “I don’t know. I think it’s nice. There’s no trailer meth bombs going off. That’s always good.”

Her eyes immediately go to the decade old burn scars running down my left arm. I think I made her feel worse.

So she changes the subject. Kind of. “So, you’re sure you want to keep staying with me, here? You’re sure you don’t want to stay in a dorm?”

“Do you want me to stay in a dorm?”

“Not if you don’t want to. You know you can stay with me as long as you want. I just didn’t want you to feel trapped.”

“I don’t. I would feel trapped in a dorm, though. People are weird. And there’s no escape in tiny spaces like that. I don’t mind the drive.”

We head back to the house, the biggest one, the one on the hill, the one that never floods. Before we can cross, a mud-spattered Chevy flies around the curve, Rebel flag streaming, blasting some early 90’s hillbilly rap.

“Asshole,” Aunt Am mumbles.

It makes me giggle when she swears.

•

I’m super-psyched for Christmas Break this year. My first semester of Pre-pre- Med behind me. I mean, really it’s classes for my A.A., but same difference, right? I was going to go for nursing like Aunt Am, but she said aim higher. She says the doctors are a bunch of fools, and it would make the nurses lives easier to have a few good ones there. She said I’d being doing them all a favor. We’ll see.

Anyway, I’m extra excited this year because we have a real tree. A Spruce Pine! The old artificial tree was officially done for, and really a safety hazard. It was like an inverted Iron Maiden. AND when I showed Aunt Am the data proving that real trees actually had less of an environmental impact than the fake ones, she was all for it.

When it’s all done and lit up, I pull her outside so we can see it from the window. Tomorrow I’m going to do the outside lights.

“Let’s go take a walk and see everyone’s decorations,” I say. The purple-grey dusk has faded to black, and my crickets are scratching a steady beat. Perseus will be out soon, I’ll have to remember to look up.

“Alright, let’s do it.” She buns her hair up in a purple scrunchie, pulling the chocolate and silver hairs back from her face. Even though it’s December, it’s kind of hot outside. It always is around Christmas. That is one thing that bugs me about North Florida. It never gets cold until January, and then who cares? Christmas is over.

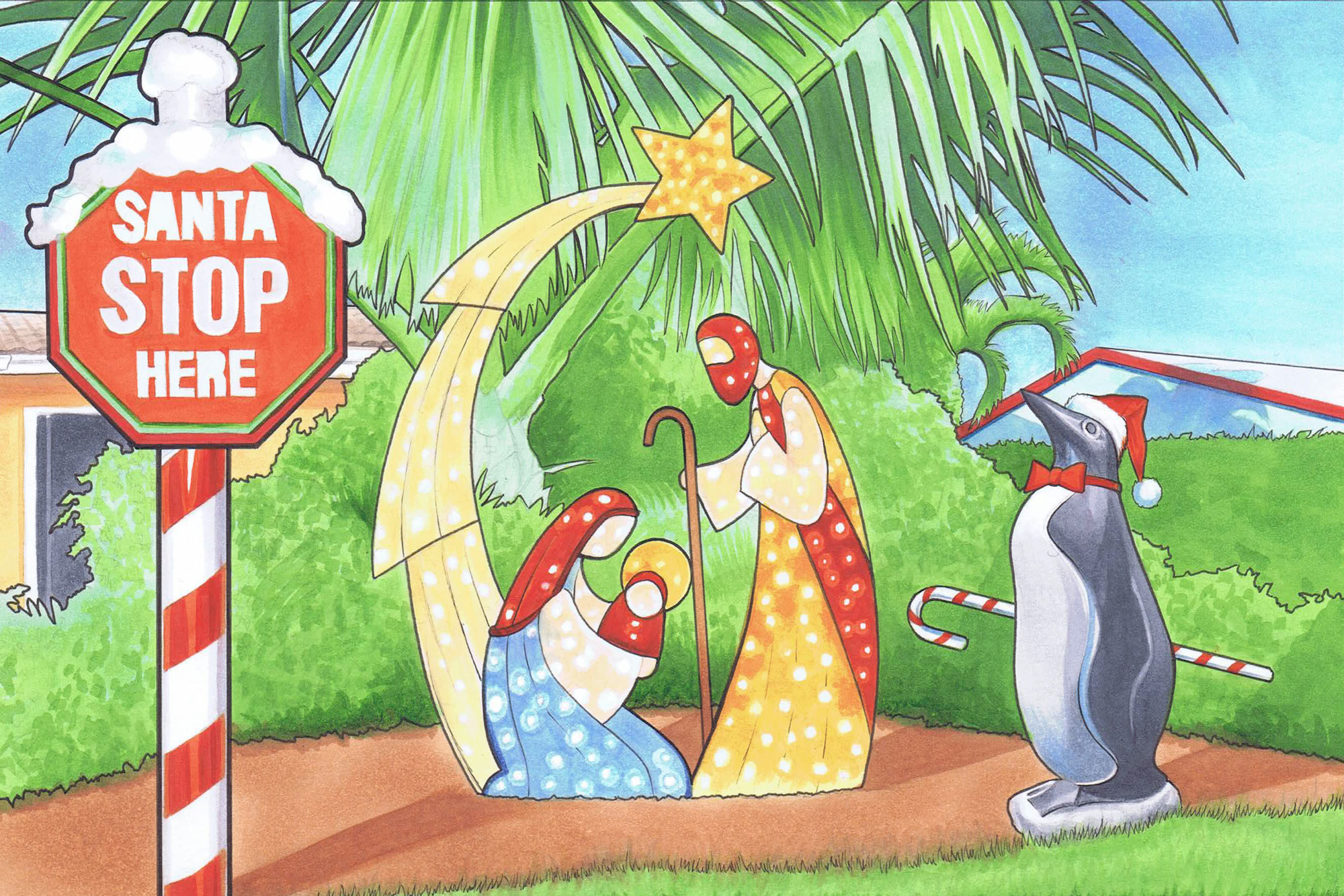

Up and down the dirt roads is an electric orgy of religious confusion. I love it. There’s a ‘Santa Stop Here’ sign just above a glowing manger. The third wise man looks a little tipsy so I straighten him out, while Aunt Am hisses at me to “Get off those people’s lawn.” Ghostly reindeer eat grass in stilted zombie motions and mismatched blinkers abound. There are some mathematical geniuses in our ‘hood, too. People whose crisp colorful bulbs form orderly rows across the roofs and around the windows. I’m thinking of what carol I should burst into, when Am makes a really aggravated noise in her throat.

“I’m sorry Christmas lights offend you so hard.” I’m kind of confused.

“The Shed People are getting out of control.”

Oh . . . The Shed People. Shed People are a Woodson Park phenomena. Especially since the economy went to shit.

I follow Aunt Am’s stiff gaze past wood fence laced with chicken wire. The already tiny backyard has been devoured by a squatty wooden storage shed. A window AC unit hung precariously from the side window, illuminated by a soft glow from inside. Someone’s living there.

I shrug. “I could have been a Shed Person.”

“You could never have been a Shed Person,” she reassures me.

But, really, that’s not true. I could have easily been a Shed Person. If my Dad hadn’t blown up our trailer when I was thirteen (don’t drink and meth, kids), I would be well on the road to Shed Personhood.

Aunt Am’s not really my aunt. She’s just a really, really nice nurse. We’d already met a few times before that last accident. She was the one that helped me when I had the broken collarbone. And when my shoulder got dislocated and nobody could get it back in. She would let me borrow her Kindle, even download books special for me.

But, that last time, when I almost blew up, that was it. Third time’s the charm. No more going home for me. Aunt Am already had full licensure to foster, and had me placed with her. She said she liked me because I’d rather read than watch reality shows.

When I was fourteen, it became really clear to everyone that I was never reuniting with my birth family. Aunt Am adopted me, and I was glad. I’m still glad. Glad I’m not a Shed Person.

Because really, if I wasn’t here, I’d probably be banging together a Home Depot domicile on my cousin’s back forty. Her husband’s a creeper, but they’ve got a lot of land.

“No, it’s true,” I tell her. “If you hadn’t of scooped me up, there’s no way I’d be in school right now. My mom would have pissed her pants if I told her I was thinking of going pre-med. I’d have been out on my ass at 18, and fast food pays just enough for a state-of-the-art deluxe storage shed.”

“I don’t believe it. You’re different.”

“Maybe so. But it would have been real easy to end up the same.” I straighten the wreath on a nearby mailbox, strangling the red velvet ribbon into symmetrical submission. Way too many feels in this conversation.

“You should rescue some Shed People. You got dogs and girls, why not take in some more strays? Culture them up-give them a future.”

She just stares at me, blinking.

I burst into my favorite Whitney power ballad, replacing “children” with “Shed

People.” I go deep on the last note and my voice cracks like a 13-year-old boy.

She laughs, and we don’t talk about Shed People anymore.

•

Aunt Am is hot. She went to Wal-Mart today, to get some Valentine’s for the kids at the hospital, and I guess she must had a run-in with a hillbilly hate monster. Unfortunately, we do have quite a few of them out this way. I’m usually pretty good at avoiding them. Her, not so much. She’s had quite a few head-on collisions.

“That poor kid that stocks the shelves was almost in tears,” she fumed. “It just broke my heart. This man, I wouldn’t even call him a man. He was just a hulking mass of beef and dip, sprinkled with beer sweat. He was a nothing, but would not leave that boy alone. Like, he actually had something to say to him.”

“So what did you say to him?” I know she said something to him.

“First, I tried to be polite.” I raise my eyebrow.

“I did! I just asked him if there was something that he needed, because if not, he needed to move on. But then you know what that troglodyte said to me? He said, ‘Well, ma’am, when I see a faggot in our community, I need to call him out. It’s my duty.’ Really, that’s what this man, in the 21st century, said to me. To my face. Out loud.”

“So, what did you say?”

“I told him, ‘When I see an asshole in my community, I need to call him out. Sir, you are an asshole, now get the hell out of our way.’”

I giggle, because cussing. And it sounds funny when grandma-looking ladies do it. But it’s not really a funny story. I know that.

“I’m just starting to think I don’t belong here.” She sighs. “I’ve lived here my whole life, but I just don’t feel like I belong here. It’s not changing. People aren’t getting smarter, or kinder, or more aware. I thought, in the future, people would be better. But they’re not.”

“You could move to like, Portland, or somewhere.” I’m only half kidding. I think maybe she’s sick of the South.

“Portland?”

“Yeah, it might be more like you. They have coffee shops and feminist bookstores and shit.”

“Why should I have to move because people are assholes?”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right. But they’re not all assholes.” They’re really not. I know a lot of nice people.

“I know, Izzy, but the Vocal Super-Minority is killing me.”

“If you can’t beat ‘em, reform ‘em.” I say, feeling kind of witty.

“The only way reform these sons of bitches would be with a lobotomy”

“Well, not really,” I say, eager to show off my medical learnin’. “All that would do is sever the nerve pathways. It would just make them docile, but not cool. Not better. What we would need to do is reroute the pathways and change their whole way of thinking. Or . . . what about, like, a Deep Brain Stimulation? I read an article that talked about how doctors are beginning to treat some patients with Parkinson’s. They put these electrodes in their brain and connect them to a kind of pacemaker in the chest by this long wire under their skin. It sends little electrical pulses through the part of the brain that controls mobility.”

“Really, now?”

“Yeah, supposedly it helps with all kinds of movement disorders.”

“Alright, Izzy.” She smirks a little. “But how would that make people stop being assholes?”

I have an answer for everything. Seriously, I do. Call me Google. “Well, you could put the electrodes in somewhere else. I would do the anterior insular cortex, which is the center of empathy. If everybody’s empathy was on high, we wouldn’t have any problems. People wouldn’t be so worried about themselves, they’d just be trying to make things better for everyone.”

“You think so?”

“Yes! Many happy and excellent natures would owe their beings to us.” Bam! Wrapping it up with Mary Shelley Frankenstein reference, I’m on fire. She’s got to be so glad she adopted me.

Aunt Am nods, but she’s looking at me kind of funny. I don’t blame her, I guess, the whole conversation was kind of weird. I still think she should help out the Shed People, though. Some people aren’t really all that bad. They just need a little time, love, and tenderness.

•

She’s converted the garage into a studio apartment. No Shed People for us. We’re going to have Garage People. And we’re going to make them better. They will eat healthy organic food, read books, stay sober, and Aunt Am can counsel them about their options. She has a whole bag full of pamphlets and vitamins and stuff from the hospital. Yay!

So, we decide to take Artemis for a little walk around the neighborhood. Scout out some likely prospects. It’s not like a formal interview process or anything, just some friendly chit chat to size up the potentials.

I veto the first Shed Person we approach. He works part-time at the Stop-N-Save and is going to school full time with his Pell Grant. He’s just living in his aunt’s shed to save money. He’s nice, he’ll be alright, and I feel kind of like a jerk for calling him a Shed Person. We move on.

The next known shed dwelling is around the corner. It’s hard to see, though. A giant stage curtain of kudzu hangs from the entwined oaks. Kudzu smothers pretty much everything -- trees, bushes, telephone wires. It’s an invasive species from Asia, nasty stuff. Aunt Am calls it “The Vine That Ate the South.” It’s too bad people can’t eat it. Nobody down here would ever go hungry.

I peep through the kudzu looking for any signs of life. It’s pretty quiet and there’s no cars in the driveway. We shrug at each other and keep trucking down the soft dirt road.

We hear the next contender before we see him. “Well, then I’ll just effin’ go, then!”

A shrill female voice counters, “Then effin’ go!”

Aunt Am and I exchange glances. Third times the charm. We hustle down the road to get in on the action.

The man is standing at his shed door, shirtless, a can crumpled can of Natural Ice in his hand. His sandy brown hair is sticking straight up into the air, held in place with his gel of sweat. His already red eyes are blazing and his stubble is bristling like the fur of an angry cat. He looks about 45, but he’s probably 30.

The woman’s leaning out the window, hollering into the backyard. There’s a slight resemblance-they have the same color hair and she has the same square jaw, but that’s about it. She looks fed up.

My aunt sidles up to fence and calls out, “Hi there, what seems to be the problem?” She sounds a little bit like a sheriff on a Western, and I bite my lip to keep from giggling at her. They both turn and stare at her, openmouthed. She hands Artemis’s leash to me. “Why don’t you take her on back to the house? I’ll be there soon.” I’m kind of bummed to miss the negotiations, but she’s giving me steely gaze, so I take the greyhound and go. The dog, not the bus. Obviously.

•

His name’s Travis. He seems pretty psyched to be in a house and not a shed. I’m still not entirely sure what went down between the three of them, but Aunt Am seems to have worked it out nicely. He came in with two big black trash bags full of stuff, so I think he’s going to settle in for a while. And he can still be close to his sister, so that’s nice.

When he goes into his room to unpack his rubbish-chic luggage, Aunt Am goes over the rules with me. Again. Or really just the rule. Don’t go into his room.

I think I can follow it.

•

It’s getting a little lonely around the house, to be honest. Travis is up before I go school, eating breakfast. But he doesn’t really say anything to me. I try to say good morning and make conversation, but he keeps everything to one-word answers. I think maybe Aunt Am told him not to talk to me too much. She doesn’t really trust people, and I am a hot number.

But it’s worse in the evenings. After we eat, she grabs her big duffel bag from the hospital and heads off to the garage with Travis. She’s trying to help him sort his life out, so they’re doing a lot of talking and reading and goal setting. I think she’s trying to get him into college. She gave him an FSU baseball cap to wear, and he never takes it off. It’s getting kind of boring.

•

Aunt Am is beaming at Travis over the fried chicken. She’s really proud and excited, I can tell. It’s the way she looked at me when I got Honor Roll the first time, or when Artemis started eating.

“I think that’s a wonderful plan,” she gushes.

He shyly adjusts his FSU cap and blushes. “Well, you’ve done so much for me here. I’d really like to start giving back.”

“Are you running for Miss America?” I ask. I’m sorry; it just sounded so cheesy. I’m waiting for him to say something about world peace or ‘for the children.’

Travis looks hurt. Aunt Am glowers.

I take it back. “Kidding! I think it sounds really nice. Tell us more about it.” See? I care.

“Well, until I find work, I just figure I might as well spend my time at the Shelter. There’s a lot of folks out there that don’t have nice homes like this one.” He gestures grandly. “So, I reckon I ought to pay it forward. Help with food and cleaning, maybe fixing up. I’m a pretty good handyman.”

“That’s really great,” I tell him. I mean it; it’s really sweet. His face lights up.

•

I don’t know who put Travis in charge of Search and Rescue, but now he’s the one bringing home strays. He met this guy at the shelter, Rick, who he says is just like he used to be. He says Rick just needs some help from Aunt Am, and he’ll really pull his life together.

Aunt Am’s excited. She ran right out that day to buy another single bed and set of drawers for the garage. She says she can’t wait to get to work on Rick.

When Travis brings him home, I don’t really see what’s so great about him. He’s got really heavy angry eyebrows, like in a cartoon, and he smells like an ashtray in a sweat sock. He doesn’t really answer when you talk to him, he just grunts. And I swear he’s always looking around the room like he’s casing the joint.

At dinner, Aunt Am and Travis make small talk, trying to draw Rick in. Each time, he just grunts and shovels more food in his mouth. At one point, he tries to rub his foot against mine, so I kick him really hard in the shin. He doesn’t even flinch.

After dinner, I half-expect Aunt Am to tell him that this isn’t working and he needs to go. I should have known better. She just grabs her duffel bag full of inspirational paraphernalia and all three of them head off to the garage.

I try to start writing my paper for Western Civ., but it’s just weird and quiet and lonely in the house. It’s not fair really. And when you think about it, it’s not even smart. I am a fixed person, so I’m the one that knows about fixing people. I’ve been fixed way longer than Travis. I think I have a lot to share about overcoming and goal setting and all that.

I head to the garage, eager to share my insights. Stepping into the room, I find out I’m wrong. I don’t know anything about fixing people. Not like this.

It looks like an alien abduction scene. Rick’s reclined in our beach lounger, his head encircled in a medical halo veiled with plastic wrap. Aunt Am and Travis are standing behind him, shrouded in papery blue masks and caps. Travis is holding a wire, and Aunt Am is holding a small drill. Rick looks dopey, but he’s awake. He smiles at me and give me a thumbs up.

I can’t even. So, I turn around and leave.

About an hour later, Aunt Am comes out. “You really are a genius, you know? It was all your idea.” She smiles at me. Tries to hug me. I step back.

“Yeah, but I was kidding. I didn’t mean actually cut into people’s skulls and screw with their brains. I thought we were going to help people for real.”

“I am helping people for real. Just think what this could mean for the world. There’d be no more crime, no more war. It works, Izzy, it really works.”

“You didn’t even tell me what you were doing. You didn’t even ask me.”

“Oh, honey,” she says in a low, soothing voice. The voice she uses when she’s trying to get Artemis to take her heartworm medicine. “I was so sure you knew; I thought you’d be happy. Think how much better Travis is now.”

“It’s not right. You’re taking people’s real selves away. You’re playing with their minds and it’s not okay. You didn’t do that to me.”

“You’re a special case.”

“Yeah, I feel like a real special case right now. This is so messed up!” I tell her. But I don’t just tell her. I scream it at her.

She turns white. I’ve never screamed at her before. I’ve never even disagreed with her before. “I’m going to bed,” she says quietly. And she does.

•

Aunt Am doesn’t get up the next morning. Think it was a heart attack, maybe a stroke, but probably a heart attack.

I take Rick and Travis to the bank, and withdraw a couple thousand from the account Am had set up for me. I split it between the two of them and drop them off at the Greyhound. The bus, not the dog. Obviously.

I don’t think they’ll say anything about us. Rick’ll disappear with his cash, and I’m pretty sure Travis feels sorry for me. He’s a super-feeler now, that’s for sure.

I’m relieved when I get home. It’s just the two of us again. Well, three, including Artemis. Poor dog. She’s laying on the bed next to Aunt Am, crying in short and wheezing whimpers. Her long nose pokes at the hardening body, trying to wake her up. She doesn’t though; it doesn’t work like that.

I’m not really sure what do. Aunt Am’s duffel bag is lying on the floor next to bed. I’m pretty sure I know what’s in it, so I start digging around. It’s not really inspirational paraphernalia, of course. It’s a bunch of crap from the hospital: wires with electrodes, pacemakers, batteries, drills, scalpels, masks. Everything you need to build a better human.

I shouldn’t have yelled at her.

I want to tell her that, but she can’t hear me if she’s dead. I empty the bag out onto the floor and start sorting through everything. If she could build a better a human, surely I can rebuild one. Right?

And, anyway, I promised I wouldn’t bury her by Hardee’s.

• • •

Copyright © 2016 J. G. Formato