Why don’t I exist?

I tried to ask the Mayor the day he dedicated the Great Wall of Denver. White-haired, ruddy-faced, bespectacled, he stood behind a podium at 180th and Colorado Boulevard. It was a hot humid day with a big crowd and several faintings. There were humans and there were bots. There were greenzies protesting and rich fatties shaded by parasols. There was a band in military blue that played Sousa marches. I approached the Mayor’s podium from behind, rolling carefully across the ancient Walmart parking lot, my treads sinking into the self-healing asphalt, leaving a diamond pattern which vanished after a moment.

“Big wall, Denverites,” the Mayor said. He was a modern man who spoke without verbs. “The second-biggest storm wall after New York’s Waterwall. Vast. Imposing. A towering, flowering edifice. Awesome and God-like.”

He said some more things about the Great Wall, its height, five-hundred meters, its intent, to block the Chinook winds from the Northwest which seasonally brought their tornadoes, its construction, the carbon-fiber panels which could be extended from or collapsed back into the support towers which rose at quarter-mile intervals on a semicircle running between the cities of Thornton and Westminster and Arvada. As he talked, the Wall assembled itself, panels spreading out from the towers like giant fans. The Wall as it spread closed reflected the late-morning sun with a pearly opalescence. The Wall echoed the Mayor’s speech with a ten-second delay.

I got closer to the Mayor. The podium was atop a set of temporary bleachers. A pair of humans, aides-de-camp of the Mayor, together with a giant roboguard, eyed me suspiciously. The roboguard was a three-headed cerebrus model tall as a house. It snarled and snapped at me so I stopped. “It’s crucial that I speak to the Mayor,” I said.

One head snarled again, its teeth like obsidian blades. A second head growled and spat steaming saliva. The third head said, “I know about you. You’re the doombot.”

“My name is Jeremiah. I have questions for the Mayor.”

“He’s giving a speech.”

“When he finishes can I speak with him?”

“He doesn’t have time for you,” said the head.

“Can I wait?”

In answer, the second head spat again, the saliva hitting my thorax. It inflamed my plastic skin, and I rolled back out of range.

“Leave him alone,” said one of the aides-de-camp, a man named Brech, whom I had interacted with before. “Doombot’s harmless.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Can I speak to the Mayor?”

“He’s busy. Tell me what you need to say, and I’ll get it to him.”

“As you wish.” I bowed. “Tell him my name is Jeremiah, and I have these questions. Does he know that Denver is doomed? Does he realize the Great Wall will fail to protect the city? Does he know why I don’t exist?”

“Huh? What’s the last one?”

“Does the Mayor know why I don’t exist?”

Brech smiled. He had fleshy lips and a tiny nose. “That’s a new one.”

“Do you know the answer?”

“You’re right here,” Brech said. “You exist, obviously.”

“I exist, in that my body takes up space. But why do I have no self-awareness?”

Brech considered. “Maybe because you’re just a machine?”

•

I used to exist. I used to have experiences. Maybe I was a man before? Maybe there is a consciousness module in my head which no longer operates? A crucial circuit which burned out or a software subscription that lapsed?

Or maybe something in my robot brain has shut down out of horror at the bad things that will happen to my beloved city of Denver.

•

Have you ever seen a Robbieville?

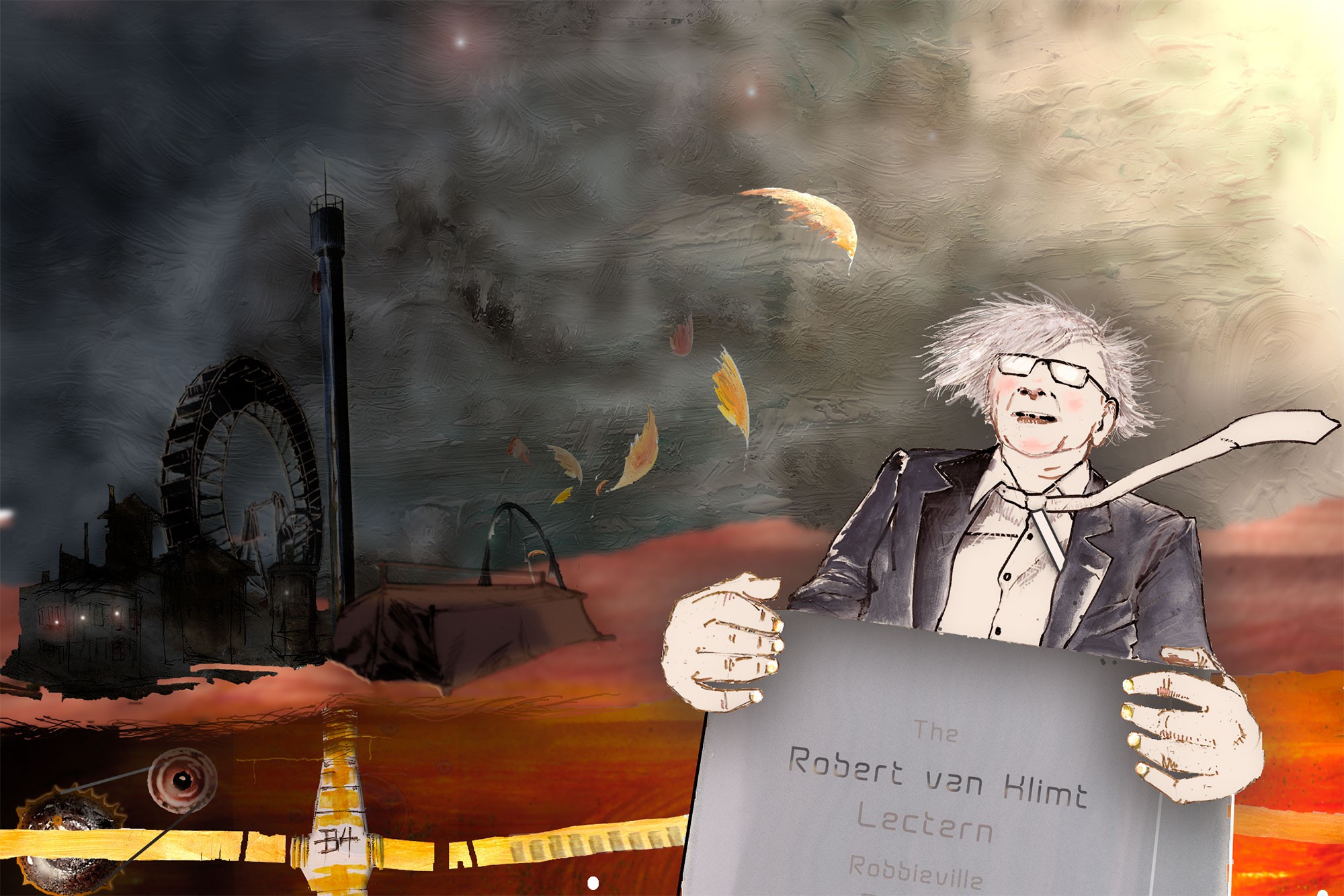

Named after Robert van Klimt, the last President of the United States, they’re the camps where bots, downsized and obsolescent, have gathered since the Great Contraction. There’s one in every city. Denver’s is adjacent to downtown, in an abandoned amusement park called Elitch’s.

I rolled into our Robbieville at dusk. Evening winds made the Ferris Wheel creak and the Tower of Doom sway. The Great Wall of Denver was open, support towers flashing red. Apparently, sunset winds weren’t bad enough to warrant closing it.

“What’s the good news?” asked Spike, the jarheaded musclebot who lived next to me in the Mad Hatter spinning ride. Spike’s head was the size and shape of a pickle jar and transparent, so you could see the solenoids and motherboards inside it. Though he had a small head, he sat in the biggest hat, the stovepipe.

I stood in the derby. Its seat had been removed so I could stand on the floor with my treads. “The Great Wall was dedicated today,” I said. “Did you know it will fail?”

“We’re all gonna fail someday. You know my head got shot off once?”

“So I’ve heard.”

“I got a new one,” Spike said to me. His eyes looked big since you could see the entire eyeballs. “The lesson is, most problems you can fix.”

•

In the evening, I saw the girl.

Lightning flashed white and purple above the brooding Rockies. You could smell ozone and sense the web of the Security State like sticky threads of binary digits. The Wall was still open though the winds were stronger and Chinook-warm. From somewhere in the park I heard human laughter.

Have you ever heard laughter?

It’s like the peal of bells, the babble of brooks, the snorts of pigs.

I rolled off to investigate.

The Witch’s Broom was running again. It spun round and round. Tinkle-tinkle music played, harmonium and mandolin. LEDs flashed, red, orange, yellow. The big robot witch-head atop the ride’s center pole cackled. Green face, pointy nose, pointy black hat, black wart, on the cheek, which opened up to sing sometimes. The Witch’s Broom was a kind of merry-go-round. Mirrors in the center column reflected your true self. Three bots were riding the broomsticks tonight. Up and down as the platform rotated. Steel bot arms and hands like carbon pincers and expressive humanoid faces. Iron hair and tungsten feet.

Only they weren’t bots.

The mirrors reflected their true natures. They were humans, not bots. A white boy with blond hair, a caramel-colored boy with wiry musculature, and a girl. A brown-haired girl with green eyes and a heavy chin.

Seeing her, I existed for a moment.

I remembered the time in the pond, when we splashed each other. I remembered when we hiked to the Buddhist temple atop the hill. I remembered when we bought hot dogs from the street vendor on Robot Plaza.

I remembered the old mudhole, with the leeches. And the Jesus lizards walking splayfooted on the surface of the water.

There was a nasty creak as we were plunged into darkness.

There were excited cries, and screams in the distance.

“Power outage!” one of the young people shouted from the Witch’s Broom.

The ride had stopped turning.

“A big one!” someone else shouted approvingly.

I looked to the northwest and saw a blanket of darkness, bordered by the Wall, which was closing, its surface lit in a grid of red luminescence.

It looked like a giant net about to capture the city.

When power resumed a few minutes later—there were no emergency generators at Elitch’s—they finished the ride.

Down came the three humans, climbing off their broomsticks. They saw me watching and all seemed interested in me. The boy, who was white-haired beneath his steel hairpiece, thrust a rotocuff carbon-silicon hand at me. I shook it. Its texture felt like a robot hand, but it trembled in a way typical of the extremities of human zee addicts. The boy had robo-eyes, cubical, pupils on each face of the cube, so you could never be sure it was looking at you. “Jeremiah! We want to hear what you have to say.”

He spoke as if through a vocoder, and it finally occurred to me what these people might be. “Are you homobots?”

“What’s a homobot?” said the second boy, the spindly caramel-colored one, with eyes everted like cones and a shiny graphite face shaped like Anwar Sadat’s.

“He means,” said the girl, “that he knows we’re humans pretending to be bots.”

The girl’s voice was electronically untreated. You don’t hear untreated voices often, even among pure humans; and you could hear the huskiness of her tired vocal cords, the moistness of her throat and lungs, the treble resonance of her sinuses. It was a human voice. Mucus bubbled from her nostrils.

It made me feel like I existed again. I remembered the night in the karaoke bar.

“Homobot’s not a nice name,” the boy with Anwar Sadat’s face said.

“What name would you prefer?”

“Mechanically Challenged,” Anwar said.

“Why are you here, Mechanically Challenged?”

“That’s not our given names,” the white-haired boy said. A voice like a plucked guitar string. “That’s just a euphemism. I’m named Turk. She’s Electra.”

“And are you Anwar?”

The pointy-eyed boy shrugged. “If you want to call me that.”

“Do you think you’re bots?”

Turk, the blond boy said: “Just ‘cause I groove on the robot fashion doesn’t mean I’m a machine.”

“Why are you here in Robbieville?”

“For the fun,” the girl, Electra, said. “For the rides and the party atmosphere.”

Anwar said, “She’s a joker. We’re here to express solidarity with our mechanical brethren.”

Turk nodded. “It’s a crying shame no bot can be hired these days.”

Electra took a step toward me. She touched my vinyl whiskers. “We know who you are. You can tell us all about the future, Jeremiah.”

“Like he has a choice in the matter,” said Anwar.

“Can the Ethiopian change the color of his skin, or the leopard his spots?” I asked rhetorically.

“That’s simple epigenetic tuning,” Turk said.

“Did you know the world will end before you reach adulthood?”

“Maybe we’re older than you think we are,” Electra said.

“Did you know the Great Wall of Denver is going to fail spectacularly?”

Anwar made a sound like an electronic beep. “Everything’s going to fail. That’s simple entropy.”

I found myself disliking Anwar. I have dibs on negativity.

“But we’re going to have fun while we can!” Electra said. She grabbed my hand. I have a single hand, multi-purpose, emanating from my chest. Her touch made me tingle, and I had a memory:

Riding on a canoe, me rowing with two hands, Electra, lovely, sitting facing me and holding a picnic basket. Her chin was just a little larger than the mechanical ideal but that was part of her charm. She had a little dimple when she smiled.

“You awake?” Electra asked. “I want to show you something!”

•

We passed the tent-and-cardboard tenements constructed around the Tower of Doom.

Then Electra led us to a door in the Tower’s cement base and we crowded into an elevator cage.

There were four basement levels and she pushed the button for B4.

“Do you really want to take the elevator?” I asked. “What if there’s another blackout?”

She didn’t answer my question. Instead, she asked, “Have you heard about the cold war tunnels?”

I had. “Ancient tunnels led from the state capital to Rocky Flats.”

Rocky Flats was where the United States had built its plutonium triggers for nuclear weaponry during the cold war between the former USA and former USSR. It was called a cold war not because it happened before global warming but because no shots were fired. Though it was certain there would be a warm war at some point, a very warm war indeed, and there were plans even then to make Denver the capital of the post-war leftovers. “These tunnels go to where the triggers still are.”

“They blocked up those tunnels a century ago,” I said.

The USSR capitulated to the USA so Walmart could open stores in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Electra asked me: “Do you know the tunnels are blocked for a fact?”

“Does anyone but a fool question he who is an expert?”

“The only kind of fool is one who’s afraid to answer questions.”

Coming from Anwar, I would have been insulted, but it was charming, hearing it from Electra.

“You can’t think it’s safe down in the tunnels,” I said to them.

Anwar, behind us, said, “We don’t. We’re changing our human bodies to bots because there’s radiation in Denver worse than Nagasaki after the bomb. Radiation kills our cells and twists our gametes. Makes sperm with two heads and eggs that plant themselves in weird places, like your lungs or your bladder.”

“Maybe it would be better to stay out of the tunnels,” I suggested. “If they run the motors controlling the Wall again, we could be trapped by a power out—”

“You chicken?” Turk interrupted me.

“Are you afraid to live on the wild side?” asked Electra.

No, not with Electra. She was making me crazy like I had never been before.

How can someone without self-awareness ever fall in love?

We got off the elevator at the B4 subbasement. The air smelled of loam and mildew and the sort of caustic chemicals used to keep the biogrowths in check. Motion-sensored lights made everyone gray.

“These fumes give me a headache,” Anwar grumbled.

“Thank God there’s the Love of Liberty act to ensure we’ll always be safe,” I said.

“Are you being funny?”

“I was told once that if you humans didn’t stay ironic, you’d just curl up and die.”

“So you are afraid of these tunnels?”

“I’m afraid of radiation. I’m afraid of everything. It may be why there is no me, because I am afraid of even myself.”

“You ought to be afraid of getting shot at, the way your jarhead neighbor was,” Anwar said.

“Yeah,” Electra said, “a lot of people resent bots even now.”

“When they should be in solidarity with them,” Turk said.

I thought about my friend Spike. He claimed to have seen action during the Siege of Orlando. But maybe he lied or was just confused. Spike often seemed just as confused as me. He always argued for the replaceability of the human brain. He didn’t appreciate that people needed their brains if they wanted to maintain the illusion of continuity of self. I used to laugh at him, when I still had a sense of humor. But now I wondered if he was right. You don’t really need a head if you can keep your brain pan in a secret place, say your liver or a quantum computer hidden in a briefcase.

“Hey, Jeremiah!” a broken bot sitting in an alcove called to me. “Tell us some good news!”

“Plutonium 239 is leaking three times the rate it was a year ago.”

There’d been a slight slip of a subduction fault, caused by water pumped for fracking proposes. You could see water stains on the tunnel walls. You could hear the low buzz of motors pumping water from between the tracks. I had warned them to not build a waterline from the South Platte River to the fracking fields, but who ever listened to a robot named Jeremiah?

We kept walking. Electra was brazen—she held her spine stiff and swung her arms in a swagger—and I wondered if she was on some focus-enhancement formula.

“Did you know inhaling less than a tenth of microgram of pure plutonium can result in your death?” I asked.

“Always the doom and gloom,” she said. “We have a bet, me and my friends, that we can make you say something positive.”

“What, like the number of species going extinct is declining because there’s fewer of them to die off?”

“No. Something optimistic. Something to make people feel good.”

I thought about this a while, as we came to a track. There was a single car there, powered by an electric paddle. “Did you know you can electrocute yourself if you touch the paddle?”

“A bot too?”

I considered. “Depends on the machine. Electrocution is suicide and suicide is an act of self-will only persons can engage in.”

“Sounds like you’re not a person.”

“I have no me. No self-hood. Ending my life would be no more noble than accidentally falling down an open man-hole cover.’

“Man-hole cover? Huh?”

“Well, I did fall down an open man-hole cover. People were sick of me preaching so they talked the cover into opening up as a gang of them approached me. I didn’t die, only broke my legs and ankles and conked myself on the head.”

“Well, that sounds pretty serious,”

“Maybe it was. I started obsessing about my ontology, my selfhood, after the accident. My legs got replaced by tractor treads. I had discussions with robot avatars of David Hume before I arrived at my philosophical system.”

The train was ugly. Windows cracked, upholstery tattered, old light bulbs swinging, graffiti in ancient tagger symbols glowing blue and red with actinium and plutonium. Crips and Bloods: jokes of dead engineers. Smell of decay. Every few hundred yards the train would stop and a cheery voice with an educated Scottish accent would announce our new station. No new passengers embarked.

The train was automatic so the operator came back to chat with us. It was David Hume himself, or one of his avatars, that is. He wore a plain brown smock over a multicolored waistcoat and covered his head with a handsome gray wig such as street-toughs sometimes affect. “Thought it was you I heard,” he said to me. His brogue was almost completely Americanized. “Only a robot would still be obsessing about self-hood. Most humans would be finding something else to be interested in.” He nodded to Electra. “E.G., a comely lass.”

“You’re a robot, too,” I said.

“Ah, ad hominen argument. First ploy of the mindless.”

“Well, I’m mindless. Tell him, Electra.”

“If everything you say is gloomy, then you’re as mindless as they come.”

“So there you have it,” I said.

“We’re trying to make him laugh,” Anwar said, of the three human-bots the least humorous one of them all.

“Why did the philosopher cross the road?” David Hume asked.

“I’ll bite,” Electra said. “How come?”

“Because he chose the chicken, not the egg.”

Electra snorted bubbles of mucus, but said, “I don’t get it.”

“What’s it prove anyway?” Anwar asked.

“A sense of humor can be viewed as a necessary—though not sufficient—condition for personhood.”

“Any bot can be programmed to tell stupid jokes,” Anwar said

“Well, I thought it was funny,” Turk said.

Electra moved closer to me. Anwar stared at me. His long pointy eyes made his jealousy seem dangerous, as far as I could judge such emotions.

“You’re just as mindless a Turing machine as you always have been,” David Hume said, slapping my shoulder in an attempt at bonhomie typical to his type of bot. The David Humes had decided a while back that since they considered themselves persons, David Hu-mans as they would inevitably joke, I should consider myself one too. Such ontological questions were fodder for the logical physicalists, the Dennets and the Searles and the McCarthys, and about as interesting as jokes about lightbulbs.

Hume said: “You should think about interesting things, like causality and free-will in a hyperflux quantum mechanical universe.”

I tried to respond, but I was swept up a strong memory of sharing cotton candy after riding the roller coaster with Electra. The pink cotton candy had stuck charmingly to her hair, which was all human.

We stopped at West Arvada, the last humanly-habitable region near Rocky Flats. A few homobots got on, though unfortunately more human than bot, a boy with red suppurating sores on his cheeks, and a girl with platinum tripod-feet that did little to hide her knees, puckered with the scars of excised cancers.

For a time it had been cool to live near Rocky Flats and risk cancers, but so many young people had died that a sense of survival had prevailed.

The kids all wore Geiger-counter wristwatches, and they were ticking, by chance, at sixty seconds per minute as we pulled out of the station.

The graffiti here was ironic: winged cherubs, smiling angels, a Jesus or two, even Mohammed, face covered, ascending in the heavens on his flying white horse, and a blue Brahma taking a maraschino cherry from a female admirer.

“The irony of gallows humor,” I observed. “Because to reflect on what will truly happen can be intolerable.”

‘You don’t think you’re going to heaven?” Anwar asked.

“I’m no person. I have no soul. Therefore heaven doesn’t worry me.”

Electra leaned against me. “I don’t see why not being a person means you have no soul.”

“Aristotle’s premise,” I said.

“Hah!” Turk said. “And he said women had no souls, either.”

“Death worries me,” Electra said. “I eat reparative RNA to fix my mitochondria. And I wear—” she held my hand—”lead-lined bikini briefs. For my ovaries.”

I remembered us raking leaves in autumn.

When had there been trees in Denver?

“Before you are adults,” I told them when we reached the Rocky Flats station, “Denver will be gone.”

“What do you know?” Anwar asked. “A robot?”

“They call this place the catacombs,” I said. The main subway branched off into multiple subways, all with rail lines. The other lines weren’t in operation any more, not electrically at least; workers pushed carts along the rails by hand. My friend Spike has claimed that the employment problem could be fixed if we got rid of motor-driven vehicles entirely, and had teams of bots or men pushing trucks or buses. Down each minor subway, grim, dusty, and poorly lit, were receptacles which had once held the plutonium-tipped assemblies called triggers but now, more often than not, held the bodies of children, wrapped in shrouds or encased in preservative Lucite, according to the religious customs of their parents. It was one of life’s little miracles that trigger assemblies were the same size as eight-year old children.

As we watched, three bots struggled mightily to push a cart toward the main subway line. My young homobot friends, especially Turk, seemed excited to see what was in the cart. No stiff body, no waxen lifeless form: just two plutonium triggers. What a disappointment. But their Geiger wristwatches clicked like crazy.

“And the Chaldeans, that come to fight against this city, shall burn it to the ground,” I said.

“Fuck you,” Anwar said. “We’re not going to burn anything. Homobots are peace-loving people.”

“You make us sound like pansies,” Turk said.

“Of course we’re fascinated by death,” Electra said. “Who isn’t morbidly curious?”

“I appreciate your honesty.”

“But yeah, it’s true, we’re here mostly to see what it’s like being homobots in the cradle of death.”

“No man ever threw away life while it was still worth keeping,” the David Hume said.

“Easy enough for a bot to say,” Anwar growled.

“But we are all just bots, aren’t we?” asked Hume. “Just machines following our instincts?”

“God will not strike a machine down for blasphemy,” I said.

•

But He might make an electric railcar suffer.

There had been a dead child aboard the car that we hadn’t known about. “No profit in advertising grief,” the David Hume explained. The child, a boy of six or seven, had been kept in the refrigerated compartment as the back of the car. He was brown-haired and heavy-chinned and looking at him made me feel as if he was the child Electra and I might have had, had my gonads been programmed to be functional. David Hume told the worker bots to lay the plutonium triggers beside the boy, one on each side, like the rails of a perverse crib. “I usually don’t do this. But it’s against regulations to have the triggers up where the passengers sit.”

“Kewl,” Electra said, though I wasn’t sure if was the prohibition or the proximity of a dead child that merited that all-purpose adjective.

When the triggers had been placed I noticed the wrist-watches were ticking at an alarming frequency (as it were). “We’re too hot.”

“Even with the refrigeration?” Anwar asked.

“No, dummy,” Turk said. “He’s means there’s too much radiation.”

“Not exactly,” David Hume said. “The fridge itself is putting out a few too many microrads. So all I got to do is adjust it.”

He shut the compartment with the dead child then stepped down into the rail slot. It seemed dangerous, what with the electric paddle being right there, and him standing in water that had may have leaked in when the Wall closed and the blackout happened. But he knew what he was doing and I have a penchant for seeing every glass not half empty but half full with poison, so I said nothing.

He took out a tool from his waistcoat, stooped down, and then began turning something, a lever or a screw. Then something bad happened. His long smock, apparently microfibered with some modern conductor though he appeared 17th century, came into contact with the paddle.

“God’s blood!” he shouted as he fell backward, material of his coat afire.

I didn’t think. I’m a prophet, not a savior.

He was motionless except for the seizure-like jerking of his limbs. I moved to the edge of the platform and stretched out my single arm to reach him down in the slot. I grabbed one hand and pulled him away and as I pulled him I felt the electricity going through my arms, then through my head, and in my head I heard the voice of God, who said this to me: “Desist, Jeremiah. Desist with the invocations of my name. I do not know the future myself so how dare you claim that you can know it. The world will get older and things will die but this is not news and it is not a thing that men need to hear today. Desist, Jeremiah. Desist.”

And then, smelling my own clothes and circuitry burning, remembering that I loved Electra when I was still human, I fell with David Hume onto the platform and there was only darkness.

•

Bots sleep. Bots dream. Or so they tell me. Otherwise we will go insane, just as people do, for the synaptic architecture of robots is modeled after that of men. But I have never been one to sleep. Probably because I am mad. Or maybe what I call my visions are really my dreams, only happening when I awake.

But I have not dreamed since the night I saved the David Hume. I have not heard God speak to me. Hume laughs and asks if I’m now a “Hume-anist” as he is. By which bad pun he seems to be asking if I am an atheist. But I am not. I still believe in God, even if he spares me the visions. I still pray, and will tell people what the future may be like, but I advise them that David Hume probably has a better conception.

I still believe in God, even though I doubt I exist. I am a fervent believer in my nonexistence, in fact. An A-ontologist. For I no longer have the thoughts, the strange thoughts or memories that I’d had of women, of especially Electra.

And what use existence, anyway, if I do not dream of women?

What use existence if there are no dreams of love?

• • •

Copyright © 2017 David Ira Cleary