Her name is Dust. My name is Bone.

How should I start my story? One day Dust felt fine, the next she felt a lump. Is that how you want it? Like those screwy healthcare adverts on TV that pretend to care about your shit. And the ending . . .? She wades out to the high water mark, searching the horizon for that last wave, and waits.

So that’s the real start and the end. Life’s like that: it’s mostly middle, mostly in-between; stuff that happens while you’re making plans to do the stuff you’re making plans about, and in the end all you’ve got is . . . dot dot dot question mark.

Something you don’t know about Dust is that she’s composed of soil, volcanic eruptions, and pollution. I think that’s why she has such large mood swings. When she found me I was steaming wetly in a shut shop doorway at sunset, geese flying south in an arrowhead. It had just stopped raining and she was walking down High Street in Belfast leaping over puddles with a petrified roundness to her blue eyes, and I asked if she was lost. She sat next to me and we talked till dawn and every time it rained she cowered next to me under my tarp, shivering like a sick cat. I was homeless then. But she saved me.

Anther thing you don’t know about Dust is that she was dead at least once before. Says sometimes she comes back and sometimes she don’t. Which it is she never knows. And I said but if I’m talking to you right now doesn’t that mean you’ve come back. And she said that maybe I’m just bat shit nuts suffering a total psychological meltdown and she’s a figment of my imagination, like that Fight Club guy. She’s always saying crazy shit like that: it’s why I love her.

Right now we were in our fifth floor flat and I spread some more powder on the mirror and chopped it up with a ruler into train tracks and I rolled a fiver up and we snorted it, her first then me. Like always.

“How are you liking the Crab Nebula?”

I don’t want to say it’s waxy and lumpy and maybe its been stepped on. “It might work if we do enough of it.”

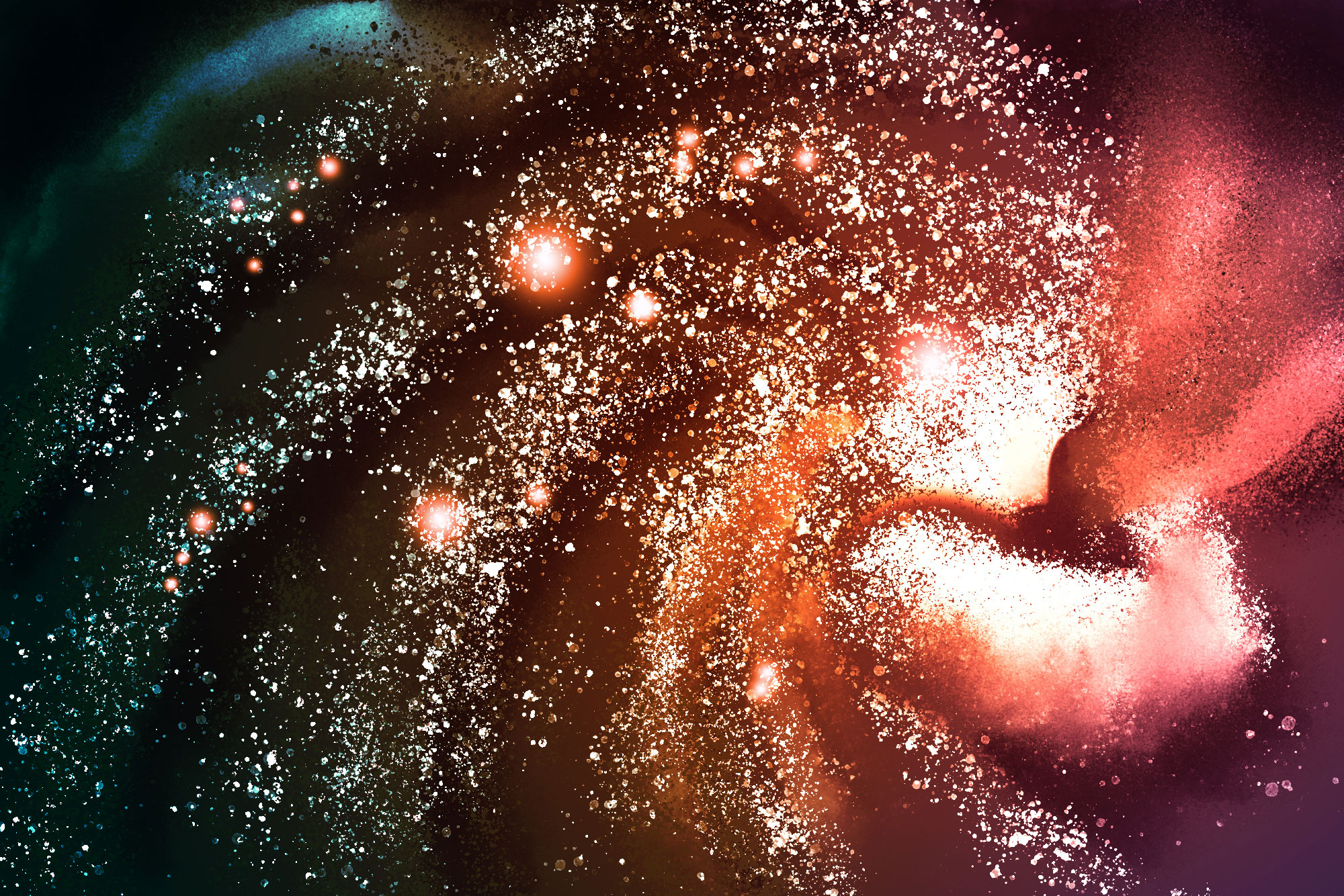

She says that we’re all made of angel dust, the remnants of the Big Bang. She has the ability to reach out into the cosmos and bring back a handful of space dust and on weekends we snort the powder, but just enough to trip. She can call the dust anytime but it takes a toll. She does it just for me because I’m worth it. And one day when she has called too much, she will turn back into dust, and I’ll never see her again.

I don’t want this to happen.

I love her and she loves me and that’s all that matters.

But it isn’t.

One day she’ll disappear into dust and every time I think about it I cry, but I can’t ever let her see me cry because she’s morbidly afraid of water, which is amazing because we live in Ireland and it rains every other day. She says this country would be perfect if they’d just put a roof on it.

Right now she reached out into the cosmos and brought back Andromeda powder. Andromeda is my favourite but it’s the hardest for Dust to collect and now she fell back onto the couch, eyes rolling in her head, whole body twitching and spasming. I rolled a tea towel up and placed it in her mouth so she didn’t bite her tongue. The Andromeda powder sparkled like ground up diamond, darkled like those vegetarian vampires from Twilight. Dust stopped seizing and I cut us two lines and we snorted, her first and then me. We travelled through space and time. She showed me the beginning and the end of it all. We are become infinite.

I sneezed, just like always, and we were back in the flat again, having dropped out of the journey. If I took antihistamines it would last longer, but Dust won’t let me take antihistamine tablets. If I do she’ll disappear, which is what happened when I took one the other week. She had been sitting next to me on the couch and became translucent, her essence winding away like smoke, swirling off like sand stripped from a desert dune. She was dissolving into nothingness. I had to do something. Anything. I took a breath, cleared my mind, knew what to do. I got cups, bowls, any container I could find, and trapped her dust in it; the rest I vacuumed. The bowls and the cups and the vacuum vibrated and shattered, and those particles reformed in the middle of the room, Dust floating there ethereally like a map of the beautiful dead stars we stared at from the roof each night. I don’t know how I knew to do what I did, but I just did. She says I’m like that—intuitive.

But I hadn’t been intuitive about the antihistamine tables I’d taken. I needed to be more careful. Dust is mostly pollen and burnt meteorite. I’ve always had hay fever and in summer my eyes can swell shut, but I’ll never take another antihistamine again. Dust has had to make sacrifices too. I’m allergic to shellfish and now she won’t even walk past a fishmongers in case even a microscopic particle of mollusc might transfer from her and send me into anaphylactic shock.

When Dust had reformed enough to be able to speak, she said, “Will you get the rest of me from your glass of water?”

I noticed her leg was missing, and that a thin layer of dust had settled on my beaker of water. I emptied it into a pot, where it became an oily paste, and I boiled off the liquid to leave a residue of powder. She called it to her and became fully formed now. While dressing she found a lump. That’s when she told me the bonds holding her together would one day soon weaken. Then she’d be gone.

“That’s just the way it is,” she said. “I don’t have long left.”

That was a year ago.

This morning, Dust had been unwell and I brought her toast in bed before I went to work. It was a clear autumn morning and I reached into the bin outside City Hall. Found a lemon Fanta tin, my favourite because of the bright yellow colour. I’d collected a half-dozen other cans from the bins, and now I laid my tarp near the entrance gate to the grounds, arranged the cans from light to dark, and sat down.

A square-faced man in a cheap suit and unpolished shoes stopped and stared. “You’re dirt, you human piece of shit,” he said. “Get a job. Stop being a sponge.”

I wasn’t a sponge. I didn’t rely on hand-outs from the government. I don’t earn much but I still work for a living.

I used a pair of tinsnips to remove the top of the Fanta can, and then I sliced vertically into half-inch strips. I flattened the strips, weaving them into a star-shaped lip around the base. Some people used them as ashtrays. Some people would toss their loose change on my tarp, and others would watch me work then walk off. Mostly people paid a quid for one. In ten hours I could earn maybe twenty pounds.

Officer Baxter crossed the street, thumbs hooked on his utility belt. He leaned into me and sniffed.

“You’re reeking of methylated spirits.”

Which was untrue. “Last night, got so drunk I think I absorbed a little part of a Navaho spirit.”

Baxter chuckled, and ran his hand though his wiry red hair. “Collect your trinkets and move on,” he said.

I said, “I’m not doing nothing illegal.”

“We have this conversation every day. It’s boring me now. I told you to sling your hook, find some other street and sell your shit to the locals.”

I continued weaving the strips of tin can and Baxter grabbed me by the scruff, stood me up and threw me against the iron railing. He grabbed my tarp, stuffed it into a bin, and dusted off his hands. I collected it from the bin and went off. A bunch of teen girls with Frappuccinos watched in unison like meerkats.

I headed towards my flat near the River Lagan, walking east along High Street. Harold was squatting in a recessed emergency exit. He was in his sixties, bearded, with a patch of eczema on his cheek. I sat next to him and caught the ripe smell of tanned leather. He took a nip from a brown pint bottle and passed it over. I took a sip and my throat sizzled like a hotplate. Must be a hundred and twenty proof. Somewhere between vodka and petrol. Stronger than spider web.

Harold had been drinking poitín he got from cousins down the country. Good for getting drunk and healing cuts. “Distilled from the finest Dublin Queens.”

Which is a type of spud; at least I hope he meant potato and not actual queens.

I only had some loose change on me, but I gave Harold what I had. As long as I’d known him, he’d always slept in that doorway. Sometimes the charity workers would harangue him, want him to spend the night in a hostel, but he wouldn’t go. He liked looking at the stars.

That night Dust and I went to the flat roof of our building to watch the stars too, that sky blackly infinite. Looking over the harbour towards the east, there was a faint triangular glow that extended from where the sun would soon rise, that diffuse light stretching along the zodiac. It’s caused by scattered space dust.

“That’s where I’m from,” she said.

The next morning, a tapping at the bedroom window woke me. I live on the fifth floor. I opened the blinds and on the ledge was a glossy blue swallow with a deeply forked tail like party streamers. I opened the window and the swallow entered, swooped around the room, landed on top of the wardrobe and eyed me. He did this every morning. He should have begun his migration to Africa by now but had obviously decided to stay with me.

Dust had saved his life. For me.

We had been walking around Victoria Square, which has a glass wall that this bird smashed into. Killed outright. A security guard had lifted the corpse and tossed it in a bin, on automatic. He said this happened at least twice a day. Then he went off. I shouted after him, demanding to know why something couldn’t be done, and that’s when I noticed Dust had taken the dead bird between her hands, her eyes screwed shut.

She opened her hands like a magic trick and the swallow took flight. Her legs gave out and I grabbed her to stop her falling. She’s been coughing much more since then.

And now every morning at seven o’clock, the swallow wakes me in time for work. I noticed Dust wasn’t in bed and her side was cold. She wasn’t anywhere in the flat. Sometimes she just disappeared like that.

Dust calls me Bone because I’m so bony. She always telling me I should eat more, which is good because I’ve grown so accustomed to always being hungry that I don’t eat so much any more. We’re great together. Dust & Bone. I’m twenty and she’s a million-years-old.

We’re the same:

I have no family and grew up in an orphanage. Her siblings are subatomic particles and never call her to chat, although I think the main reason is because they don’t have mouths.

On my hip I have a small birthmark like a swirl. Dust had said it was the Milky Way—a perfect Fibonacci spiral. But I said, Isn’t the Milky Way a chocolate bar for kids? She laughed. I loved her more because she always laughed at my silly jokes.

So I have a birthmark, but Dust has a lump. Several lumps now. Sometimes on the buttons of her spine. Sometimes on her wrists and elbows and joints. Sometimes they’re like moles, other times it’s like she has freckles. A year ago she had none.

We’re the same but we also have our differences:

Dust hates water. Most people when they wash, they take a bath; Dust uses a bathtub filled with fresh soil. It means I have to wash in the sink, which I hate. But that’s just the way it is.

I entered the kitchen to make tea and I put out a bowl of seeds for the bird. I sat on the couch and outside it was still dark. The beauty of this time is that you can watch the whole city wake up, each streetlight winking off as the sun spread across Belfast.

There was a shadow on the wall that connected to the bedroom. The shadow stretched into the shape of a human, and Dust materialised out of the wall like she had walked through it. I’d never seen that happen before. She sat down next to me, laid her head on my shoulder, and nuzzled up.

She said, “There’s a science to walking through walls.”

“What is it?”

“I don’t know exactly,” she replied. “I’m not the right person to explain it to you in human terms.”

There is a science to walking through walls; I’d read about it in the periodicals in Central Library and it turns out that it is all to do with quantum tunnelling and subatomic particles.

“But it takes a long time,” she explained. “The smaller you make yourself, the greater the distance to travel.” It had taken her five hours to get through the wall.

She glanced at the small object in the paper bag on the coffee table. I’d bought it for her yesterday but she was already on the roof when I’d got back and I’d forgotten it here. She opened the bag and lifted out a piece of polished amber containing two ladybirds. They had died, which was sad, but they’d also been preserved together for eternity.

“They didn’t die together,” Dust said. “One of them died trying to save the other.”

The ladybirds were a half-inch apart. Forever.

I didn’t want to think about Dust and what might happen when she had to leave. We’d made a decent home here in this flat. Bought our furniture from Saint Vincent de Paul, a couple of bar stools, a fold-out couch, tables and lamps. These were things that had belonged to dead people. I liked that they hadn’t been tossed away like rubbish. Someone had loved them one. Someone had wanted them.

I had also bought a television, a beautiful ancient cathode ray model with a wooden frame. It never worked. I kept it anyway. I had taped a picture onto the screen of the Crab Nebula. The crab is for me, because I’ve always wondered what it might taste like, and the nebula for Dust because it’s the remnant of an exploded supernova in the Taurus constellation, and it’s beautiful like Dust is beautiful.

Most of the flats in this new building were derelict. The housing bubble had burst, rents were more affordable. From this window I could see across to the two giant yellow cranes, Sampson and Goliath, which had built Titanic. I don’t know why people liked to celebrate a ship that sank. I’d seen a t-shirt that said Titanic—it was all right when it left here. My favourite thing about this city was Belfast’s coat of arms: a chained wolf, and a crowned seahorse. Sometimes I imagined being that wolf and Dust was the seahorse.

Dust got up, went to the window and leaned her forehead against the glass. She stared vacantly out across the harbour at the choppy grey churn of the North Sea.

I’ve had one other girlfriend before Dust and she left me too. I’d walked with wet feet, the soles of my sneakers worn through, alongside her to the train station and onto the platform and there we stood together not talking or meeting the other’s eyes. Would be the last time we were ever together. A steam whistle shrilled, the platform emptied, and Mary Rose had gone off to make her way in the world. No room for me.

A week later Dust and I exited the supermarket. It was late evening and I had to carry all of the bags because she didn’t have the strength. I said I didn’t understand life, why it could be so cruel. She said life isn’t cruel: it’s like a string of pearls stuck in the folds of some fat lady’s neck while she scrubs her gussets in the sink.

Harold was hunched over in his favourite doorway, shivering. It had been raining horizontal all day and he was dripping wet.

“This isn’t so bad,” he said. “I can be comfortable anywhere. Just need to get off to sleep, is all.”

His fingernails were blue, lips bloodless. Then he stopped breathing. I called out for help but nobody came over. I yelled for someone to call an ambulance and I laid Harold out. He had no pulse. I’d learned first aid in the orphanage and I placed my hands on his chest, pressing hard and fast. Heard the Bee Gees’ Staying Alive. I kept at it for a minute but he never took another breath. I stood up, in tears now, and yelled for help but there was no one nearby and I noticed a payphone at the far end of the street. About to run off, I caught sight of Dust kneeling next to Harold, her hands cupped to his head, her eyes screwed shut. Smoke coiled out of her mouth and into Harold’s. He coughed, opened his eyes, sat up.

Dust smiled at me, then slumped backwards and passed out. I went to her and she was stiff. Solid as stone. Like marble. I heaved her up into my arms and stumbled with her to our flat at the end of the street. On automatic now. I lifted her into the bathtub which was filled with soil. My hands had a fine dusting of powder like when you touch a moth’s wings. I was muttering, not making sense, all I knew was that I couldn’t lose her like this. I didn’t know what else to do, so I held her hand and kept bathing her in the soil.

Her chest hitched and she began breathing.

“You can’t keep giving bits of yourself away,” I said. “Soon there’ll be none of you left.”

Not long after this Dust was staring vacantly out of the window in our flat across the harbour and out to sea. So pale she luminesced like bone china. The rupture of a horrendous scar stretched from under the hem of her sleeve. Her body had been rending and tearing itself apart.

She said, “It’s time, Bone. I have to go.”

My stomach dropped out and I lurched into the bathroom and sicked up. Then I took her hand and she led the way to the shorefront. She hadn’t explained how she would leave and I had avoided talking about it.

She pointed farther out to where the waves were breaking. “I’m going out there and I want you to promise you won’t come after me.”

I couldn’t swim. I couldn’t go after her even if I wanted to. But I couldn’t understand why she would go into the water. She hated water. Surely she should just dematerialise into dust and float off into the sky. Back to where she came from.

Dust stretched off into the cosmos and brought back some powder. “Something for you to remember me by,” she said. It was regolith from an asteroid a six light years from earth. She’d told me about how special that asteroid was. One day it would strike this planet and reset everything, just like with the dinosaurs. She’d told me that regolith was Greek for blanket. “Without regolith there’d be no life on earth. Sometimes it gives, sometimes it takes.”

“Why are you going out into the water?” I said. “Why not go off into space?”

“Because this is how it ends for me,” she replied. “I knew if I stayed here, this is how it would have to be.” She took my hand and smiled. “You were worth it, Bone.”

“Can’t you turn me into dust and we can leave together?”

“But I’m not leaving,” she replied. “I’m dying.”

She held me tight. Electric odour of burnt ozone. Belly rumble of a broken sky. Water lapped against the harbour walls, the air a tincture of brine. Farther along, rows of orange buoys like ellipses. We held hands and walked to where the harbour ended and the lough came ashore, and she kissed me, defiantly unafraid of my wet face and then she crumpled over and stumbled into the grey wash. She waded out to the high water mark, searching the horizon for that last wave, and waited.

Around her the water glowed and became reddish like rust; she was dissolving. I yelled at her, plunged into the water and went under. Forgot not to breathe and my lungs burned. I couldn’t swim but I pushed off the bottom, manoeuvring towards Dust. Taking her in my arms, I went under again, and now she was unresponsive, her eyes open and glassy. I thrashed splutteringly towards shore and the water was to my waist now and I had her in both hands but she broke apart. Her dust now became a paste and it sank, dissolving to nothingness.

I grabbed at those tendrils of her essence, regaining it to myself, and around me now the water glowed like a halo—the regolith having seeped outwards in ribbons. Now it swirled, coiling. Blanketing. Mingling with her wet dust. And I was melting too now, dissolving. We came together. Joined in a hard paste, then clay and bone ash, formed porcelain, spreading into a tincture of everything, infinite. Nothing between us now. Together we dreamed of everything that is, has been or will be, as is meant to be; in the end all is dust and bone waiting to be stone.

• • •

Copyright © 2017 Michael McGlade